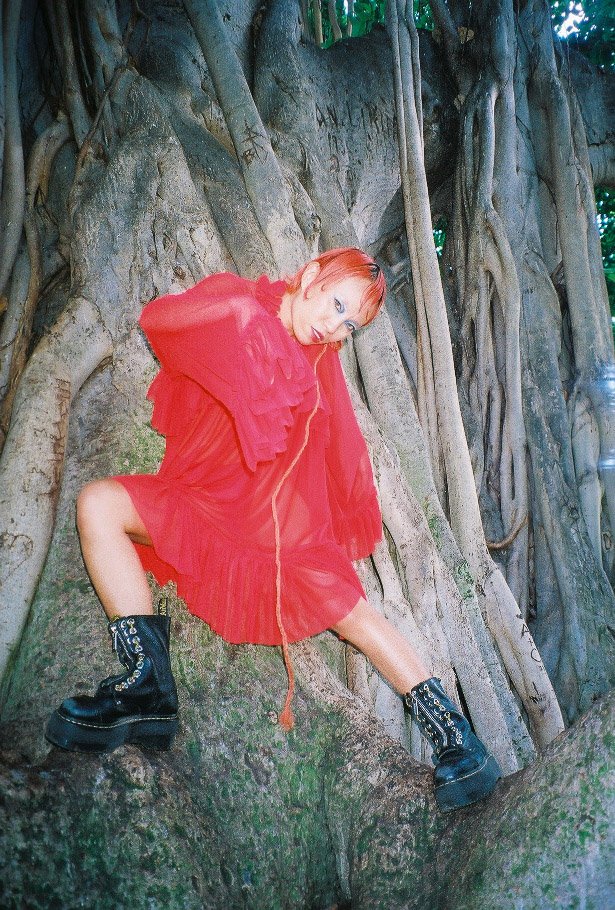

Jenny Liang

As a storytelling medium, clothing conveys facets of our personalities whether it be performative, practical, or both combined. The attire of work, of play, and above all of assimilation, the art of distinguishing oneself from others. To mold out to inward and become unassuming. The phenomenon of conception, of executing what one ideates into what one builds. We all play parts in the creation of bodies that wear, therefore bodies that choose and construct. Most of this extends to the realm of the body and its maintenance and performance: building upon identities, mediating new emotions surrounding change, and accepting when a transformation is necessary. What about the body not yet formed? The body not yet realized, or even consciously conceived, blocked by circumstances of our physical, systemic, and political environments? How may we form and develop intimacy with a connection to elsewhere?

Honolulu-born angel Jenny Liang (she/he/they) flows within an elsewhere, inspired by an itching sense of wandering fashioned into the timeless atmosphere that builds upon desires and dreams. A dance like a play in form and a form of play. Design and clothing play a part in this longing for Liang, as creating identities often come with its personal revelations in modification. Longing for landing is a feature in how clothing is worn. We must move, timing is important for not tripping on yourself.

From watching anime as a young child to modifying international trends for Honolulu’s balmy weather in adolescence, Liang has always involved themself in personal reinvention via vivid visual imagery, intimate self-mythologizing, and styles reminiscent of the many transformations seen in Sailor Moon, Madoka Magica, and Kill La Kill. As Senketsu exclaims, “the time comes when a girl outgrows her sailor uniform.” One finds freedom in their choices, even in the realms of dressing—and the opportunity to grow out of uncomfortable cliches and into something liberating and one’s own. Liang’s personal storytelling begins before their material creations. Ideas sprouting from a culmination of alienation, belonging, and devotion have all become affections which Liang carries dearly through this life.

Jasmine Reiko of Coeval Magazine muses with Jenny Liang on the distinctions between wearer and designer, the sense of arrival in one’s own body, and their imminent move from Honolulu to Los Angeles.

What’s it been like to grow up in Honolulu involved in design, styling, and fashion since you were a teen?

In one of my earliest memories, I was drawing at 3-years-old. I was constantly sketching the characters I’d see in cartoons, completely obsessed with their outfits and what they would wear for different occasions. I’d imagine myself in their world and what my own outfit would look like so you could say those were my earliest moments designing. In regards to styling and fashion on an island like ours, completely alienating, to say the least. I was embarrassed to not be wearing what the other kids were for most of my child since it was incredibly cheap there. Ironically, in my teens, I’d overcompensate for this by dressing in what I’d seen in magazines and on Tumblr which still did not align with the relaxed, casual dress common here.

What is making fashion to you? If not fashion, clothing, objects to be worn?

I use clothes as a medium to tell stories. Combining silhouettes and embellishments into something that speaks. The pieces I’m most connected to are ones filled with emotion and thoughts that are personal to me. It is giving a physical form for what would otherwise be a feeling that disappears in my head.

In Hawai’i, I feel growing up we did not have much access to major fashion trends and brands where we can just buy and become the trend we see on Tumblr or otherwise. What was happening on the continent couldn’t be reached without paying for shipping and having knowledge that it even existed. In our adolescence and young adulthood, so much has changed in Hawai’i where lots of boutiques and stores from the continent have spawned here and flourished throughout the island whether or not we engage with them, social media being a huge counterpart in that. I remember us as big thrifters when Savers was almost like an industry secret. How did this context shape your lens on consumership in Hawai’i and has it shaped your idea of styling now?

One of my favorite things about Hawai’i is that for a long time there was a slow acceptance if not outright rejection of popular fashion trends by the locals. The majority of those trends are simply not fit for a warm climate, nor relevant to the lifestyle here. However, because of social media making the world so much smaller and making the trends going on in the mainland US appear so much more important; I see a lot more locals flocking to new openings of chain stores from the mainland US, buying whatever is unavailable here online, all to participate in what the internet shows as ‘sought after’. That being said, what is available in popular stores does not serve to define the character I’m attempting to bring to life who is often not part of the world we currently live in.

photography COYOTE PARK @coyotepark

I consider you a shapeshifter in the way you are able to create delicate yet distinct pieces and don them-- to the point where when worn they become different entities on any person who wears them regardless of where they want to take them. It’s against the fast-fashion brand of abiding the apparel, ‘wear what you buy as it I.’ Where do you place yourself in the noise of the fast fashion industry and your personal creations?

I would hate to see the care and intention I put into each piece to have its life lost in immediate consumption. Fast fashion is often clothes for every day, for right now. I aim to create pieces for special occasions in other worlds, or performers of the future.

Your ability to construct and sew together pieces into a discernible identity is something that has always drawn me to your glossary of looks. Whether it be the alien in your angel set or fae in your beloved tulle sets, do you consider these different personas? If so, how do you weave between these different concepts in your work when creating anew?

I’m honored that you were able to read that in my pieces. Yes, I would consider them to be different personas. I love to imagine what a being from a different realm would wear and channel their power and energy. Maybe it’s my way of dissociating from the mundanity of regular life by dressing the part of an otherworldly being. When creating a new piece, I consider fun silhouettes and accents and how to use them in an unexpected way. I think “what sort of feelings or thoughts does this combination evoke in me?” And from there I piece together a character and tailor it to them.

I feel clothing offers something like a connection between the viewer and the wearer, and this idea extends itself strongly to our queer community. A way of expression amongst us where our presentation becomes not only a form of art but constructing bodies and other-personas. From making clothes and the process of wearing them, how does this movement resonate with you?

When wearing the pieces I’ve made, I can say I am simply wearing clothes. Not something that has ever been designated for men or women because I did not have such intentions when making it. There is something so empowering about being able to say that. I am whoever I want to be, I present in whatever way suits me in the moment.

Many of your pieces involve shibari-like tying, straps, and material resembling movement. Where do you as a designer fall from the wearer’s perspective? Where does your styling stop and the wearer begin?

It’s funny you ask that because I’ve put a friend into several of my pieces and she made the comment that all of them were nearly impossible for her to figure out how to put on alone. For me, the fun is in the complexity. The piece draws interest because of its elaborate wear. It’s a necessity for the piece to be styled correctly for its full effect. The wearer just needs to carry themselves strong enough to not be worn by the piece.

Fear is something that most artists feel both compels and deters them from reaching for what otherwise could be a renewal, something different, and/or a revolution revealing more than the now. How do you manage fear in circumstances that may reveal more? In other words, how do you reckon with the uncomfortable?

In situations where I find myself unsure or uncomfortable I just send it. I give myself anxiety unnecessarily when I stall a decision. If I just make a decision and stop overthinking I can get to a conclusion and if it turns out to have been a ‘bad’ result, I remind myself I now have the knowledge of how to do better the next time the chance presents itself.

You are moving to Los Angeles very soon. What drew you to LA? What are some lessons you will bring with you from Hawai’i to your move to Los Angeles?

My original plan was to take a few years and move to NYC but during the pandemic, I felt so stagnant and uninspired here in Hawai’i. I needed to be somewhere else I could be surrounded by constant inspiration and fascination. With the cost of living in NYC and lack of a support system I would have had there had moved out, LA seemed like the move for me. It was further solidified knowing I had extremely grounded friends out there.

photography PHOENIX TRAN @idonthaveagram

You talked with me about alienation during our shoot. Not just from a clothes-wearing perspective but the connotations that lend themselves more broadly to a kind of ‘body of assimilation.’ A body being your own, or your extensions via clothing, makeup, styling, which are also your own. Assimilation means a mode of conversion, of responding to new situations through the lenses of conformity that tends towards the comfort levels of a certain lifestyle. How would you describe your experiences of alienation, of course, unrestricted to ideas of clothing?

When I was growing up, I’d constantly be striving to assimilate to the immediate world around me, but thanks to the internet, I was exposed to so much more life and sought excitement in living close to lives different from mine. It’d start with dressing like people from different places, fascinated with clothes that were popular elsewhere to how I present now, which is being at home with that sense of other.

We also talked about how your pieces transpire notably by the feelings of being somewhere else induced by this alienation by feeling both separated from what we call “local” to Hawai’i, existing as the not-American, but also being separated from your Chinese background by being American. How does this rift inspire this vision of elsewhere, of feeling far away and yet right here, just slightly away?

I grew up watching so much TV which gave me an expectation of what American life was supposed to look like, yet it is dramatically different from what life is like in Hawai’i. And from there I felt I did not participate in much of the local culture either since my family does not have roots here. They immigrated from China and were strict and traditional. And yet to them I was American and not truly Chinese. I can fit myself places, but it never felt perfect so I gave up and allowed it to happen where it can. Even in my gender expression I feel I’m everywhere with it. I’ve found joy in the choice of performance. Going back and forth in dressing the part of a different life that exists now like a suburban stepmom or skater boy then jumping to ones I create inspired by the future or myth in cyber angels and Chinese deities.

What was the last thing you taught someone?

I taught a friend of mine how to use his sewing machine and serger. I went through it all in one sitting and was out of breath explaining identifying parts, their functions. But I find the knowledge of how to use these machines important if you have them in order to mend small holes in clothes or tailor the fit to extend the life of a garment.

photography CARIMA ROBINSON @naniifyourenasty

All photos not credited are shot and edited by JASMINE REIKO

interview JASMINE REIKO

What to read next