Connor Marie Stankard

Connor’s current show at Lubov Gallery Ava, Chloe, Blair, Nicole presents 8 paintings , 8 named girls (Laila, Violet, Charlotte, Vita, Taylor Jeanne, Chloe, Daisy, and Marla) as well as 8 glass orbs of perfumes or potions displayed on a pedestal calling to mind a carousel at Sephora.

This is Connor’s sculpture “Choose Me, Hear Me, Stuff Me, Stitch Me, Fluff Me, Dress Me, Name Me, Take Me Home.” My mind goes to playing dress up, with a girl, a doll, or something that exists in a pale area between.

These balls have the presence of luxury, like if you breathe the wrong way or stand awry in front of them one might shatter. The materials suggest they are more alive, swimming with bacterial colonies, reeking of bile ,while packing in the restorative punch of Reishi mushroom.

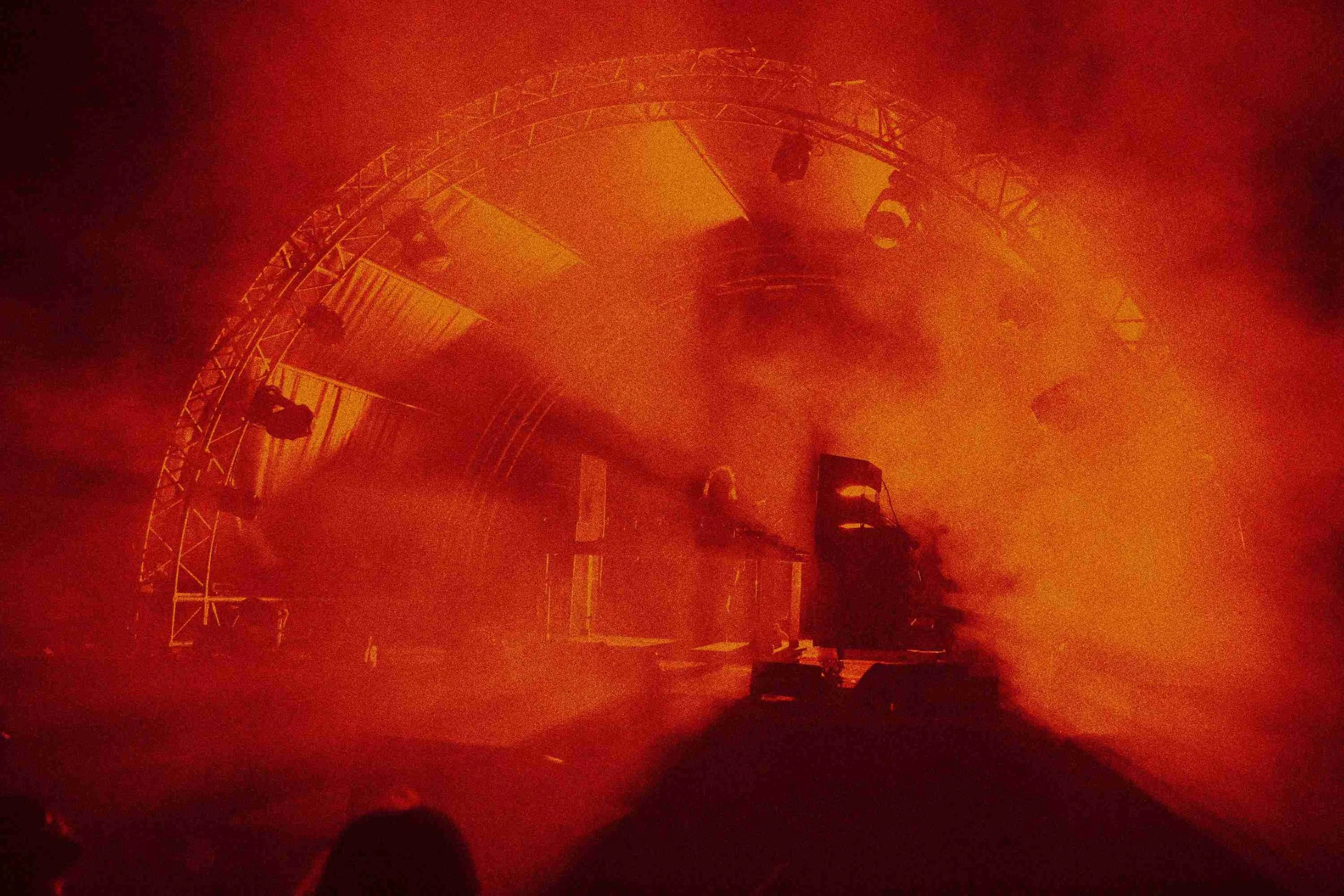

Above the orbs a video plays of a woman submerged in mud, dancing in her descent. We never see her breathe.

When we walk up to the perfume counter inside the luxury department store, it is not a certain base note calling to us, but the muse. When we take the luxury perfume home, we see ourselves as the girls in the advertisements. But, we’ll never be those girls, and now we’ve been sold a small piece of their image. Is this a parasitic relationship? That aspirational image reproducing with each spritz of “J’adore Dior”?

The aspirational is Connor’s raw material. Dior Youth Serum and chlorophyll fill her 8 perfume balls. The paintings have all sprung from the Instagram models that haunt our feeds, that advertise to us.

The girls in Connor’s paintings achieve their new form from the painter’s knife rather than the surgeon’s blade. By twisting and manipulating what is aspirational, the artist makes us aware of a true underlying perversion.

Connor refers to the figures in her work as “golems” and “creatures.” She mentions Dr. Frankenstein. The scientist in Mary Shelley’s classic began with experiments, finding divine inspiration studying the decay of living matter. He is then emboldened. Playing God, he sets out to create new life, but his pursuits lead to the birth of a monster. We never see a female companion for Dr. Frankenstein’s creation. He believes she will be too dangerous, and tears her premature body apart in a fit of male hysteria.

Connor’s implication is that the viewer is the Dr, the ultimate one to blame for these pieces being out roaming the world. However, it’s easy to look at her work and make a comparison between the artist and the mad scientist. Connor builds a larger narrative world, where all girls blend into one girl, and this girl grinds herself into dirt.

DWM: You’ve said your work begins with fear. What do you fear? How do you translate the experience of fear?

C: Trypophobia is the fear of clustered holes. It’s all about the vulnerable body and the outside coming in and messing things up. I don’t have it, but I get it — it’s freaky how porous we are. With the word “phobia” there's a connotation of irrationality — but the trypophobe is right! She's gauged that yes, we are full of holes, and that the holes do make us vulnerable.

In my work this fear is a starting point, not a goal. I don’t want to scare the viewer, that’s cheap. I want to imbue phobia with philia. Because our ability to be entered and manipulated has as many pleasurable ends as revolting ones … perfume and anthrax come in through the same door.

DWM: What stories do you remember reading or being told growing up?

C: I remember watching Sailor Moon, ribbons exploding from her chest as she transformed into a Sailor Scout, or getting injured every episode but bouncing back intact, super malleable. You can abuse pixels and reconstitute them over and over, losslessly. You can express perverse desires or frustrations onto digital images without causing damage. I’d play with that boneless bubble girl as a kid and the whole point is she’s getting absolutely wrecked, slammed around. But you only feel a little bad because she isn’t real.

Then, on the other hand, it's our nature to feel real love towards a set of dots. My Tamagotchi was only a few pixels, but once I watched him hatch from the little egg, once I named him — those dots became my responsibility. I cried tears when mine died. Same with Neopets, picking the color of your Cybunny, naming her, logging on after elementary school to earn Neopoints and provide for her ... even as a kid, sacrificing for digital images, it's beautiful.

DWM: How did you create the characters we see in your exhibition “Ava, Chloe, Blair, Nicole” at Lubov Gallery? Was there a certain spark that ignited this body of work?

C: The images begin using a GAN software called ArtBreeder which creates faces. You can edit the face’s “genes” and create “children” from her likeness, or “crossbreed” her with other faces. I love the scientific, incestuous language.

The crossbreeding makes me think of the way bacteria reproduce, where one cell splits itself in half to create a mutated “daughter cell.” The faces are related to and reproduced with each other — like Faye Dunaway yelling “my mother, my sister!” You can see the inbreeding in the paintings: the girls share features and those features pervert or smear together across the room.

After messing with her “genes” — dialing numbers up or down, the source becomes even more obliterated. Like if you tap them, they twitch into you know, something slightly different. As I’d sweep the toggles, the images completely abstract. When the “gender” toggle is dialed all the way up to girly, she collapses into pure soft pink, totally hyperbolic femininity. With the “earrings'' dial all the way up, she's just a rainbow of white glittering dots. No longer Lily-Rose or Gigi, hardly human at all.

In the end, they aren’t really paintings of people, they’re cyborgs — born, in part, by machine. They do resemble women, but as a glamor, the way an insect's wings might mimic a face.

DWM: Can you talk about the idea and concept of the muse?

C: I think the idea of a muse relies on one woman, person, thing, whatever, standing apart and above others — its about the individual. I’m interested in the opposite — a loss of concrete individuation.

The women I uploaded — the Kendalls and Bellas — were pulverized before I reached them; their likenesses turned into a medium. Which, at the same time, is a function of the muse, isn't it? To be a container, a multi-tool, at the service of, is all important to Ava, Chloe, Blair, Nicole. The gallery proposes a user-driven experience, like a Build-A-Bear. Pick a liquid, pour it into Cavity and let her cure … out she crawls.

DWM: When does the female form become a cavity? I love this piece and I feel one of the most striking elements is that the title is already an easy association. This in itself is a little jarring. Like, shouldn't it be a bigger jump to make to see a human form as only an orifice?

C: “Only an orifice” sounds like an association with passivity, but holes are rarely empty. They’re not born of nothing, they're forged from something burrowing or hiding. Trypophobes fear holes for their vitality, not passivity.

A tooth’s cavity is rot forged from sweetness. So, personifying the orifice in Cavity, casting a vessel in the shape of a woman, is just as much about soft passivity as it is about camouflaging danger. Maybe it is jarring, but I think it can be fun and sexy too.

DWM: Would you describe the relationship between the viewer and your work as symbiotic or parasitic?

C: A custom-made human object brings up a lot of questions. What does the maker’s heart desire? Do you want a nurse, girlfriend, mother, therapist, patient, wife? Why settle for one?

I didn’t fill the gallery with statues of daughters or debutantes or girlfriends because it’s the engineering process, not the final product, you’re walking in on. This binary of symbiotic vs parasitic isn’t up to me: I’m not Dr. Frankenstein, the viewer is.

Let's say you get the girl, what next … you bring her home. Is the relationship parasitic because she’s now inhabiting your space? Or is it symbiotic because she loves you back? A little bit of both, up to you.

DWM: I want to know your thoughts around the femme fatale, the relationship between seduction and the abject. I'm thinking of the story you wrote for Cloaca Palace, which fixates on the Caroline Herrera Good Girl perfume with its high heeled bottle, and the other memorable objects being a chicken carcass and shit.

C: Like ‘plastic,’ ‘vanity’ has satisfying dual definitions. It’s a synonym for ‘narcissism,’ but it’s also ‘futility,’ doing something “in vain.” We grasp at one to stave off the other. I take pleasure in myself, in beautification and seduction, even when it feels absurd to do so, given the fact of rot. This is what Vanitas painting is all about.

The glossy objects in the story, the stiletto-shaped perfume and bedazzled Prosecco bottle, and their nasty counterparts aren’t antonyms, they’re linked, because abjection sits right below the surface of seduction. The story’s plot contains a melding of the two meanings: a vain young girl physically merges with her older boss, her memento mori. The title too, Cloaca Palace, joins the abject and seductive.

DWM: What is the relationship between your written and visual pieces? Do you see your practice existing in or creating a larger narrative world?

C: The written and visual totally exist in the same universe! The story’s heroine unravels, half-dies, and the painted girls are being born, but only partially. They’re both stuck in loops: becoming and unbecoming, never fully formed. So the girls are interchangeable, it's all one girl. All the work is about shapeshifting.

DWM: Can you talk about your video “Habitat 1” where we see a girl dancing in mud, completely silhouetted by the substance? What was the filming process like?

C: I didn't film Habitat 1, it's all found footage. I edited about 40 videos from a fetish site dedicated to this specific thing of like, women being covered in liquids: paint, cream, Nutella, mud. It’s all pretty PG-13 and cheery with lots of talking and laughing, it’ not overtly erotic, but in editing out each woman’s identities, they blend into one girl, and that’s freaky. Her skin is always covered in mud, so she becomes like a golem. I also removed any intake of air, so there’s a suggestion that she can breathe into the dirt, like an amphibian. I found myself holding my breath as I edited the video, empathetically testing how long the mud girl might be able to hold her’s.

There's a Christian idea from the Middle Ages, the Great Chain of Being, which ranks living things, going from God to angels to humans, etc. all the way down to minerals — dirt. So this girl-monster is messing with that chain by grinding herself into the mud, collapsing a holy hierarchy.

The video is also a kind of dance. All the movements are cued to my friend David Hertzberg’s saxophone quartet, Murmurations. The movements and setting are reminiscent of Butoh, a Japanese dance style from the 60s. Butoh dancers are nude and often covered in paint or mud. All three: the fetish videos, Butoh, and Habitat 1 are playing with the taboo of merging human and environment, pleasurably collapsing what some ordain as delineated.

DWM: What are you trying to convey emotionally?

C: My work is for the hypochondriac who knows she's malingering and the unwashed who suspects she’s ill. Not totally Cronenberg…more like Bataille’s Story of the Eye. Discomfort that draws you in, grosses you out, and turns you on.

Current Exhibition: “Ava, Chloe, Blair, Nicole” is on view at Lubov Gallery until July 24.

Upcoming: Connor’s novella Charm Bracelet will be published in 2023.

interview DAKOTAH WEEKS MURPHREE

mastered by JAGRATI MAHAVER

What to read next