Laila Majid

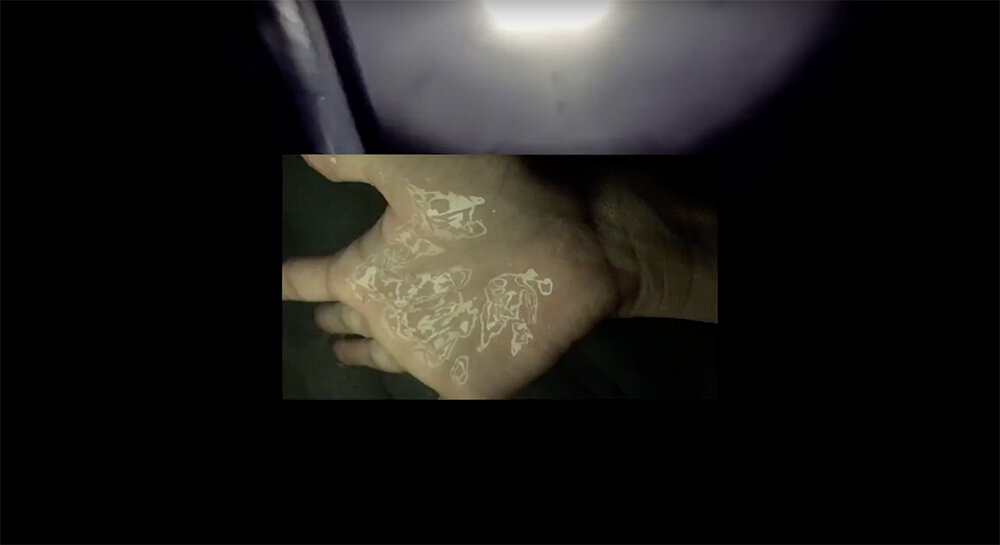

Rosie (2019) Digital image

In Laila Majid’s installations, images become palpable and reactionary. We are no longer looking at a 2D image, but feeling its texture (most often gooey), smelling its scent, or listening to its sound. Through physical and digital manipulations, Laila creates images, videos and objects where the body (human or not) is often the study subject — saliva, skin, eyelashes and eyeballs are documented and distorted through the most unusual processes and perspectives. Hands become paws, or sometimes claws, flesh becomes fury or completely bald — the body is shown in constant mutation and is full of possibilities.

In our conversation we discuss about the current digital image culture and imaging technologies, social media changing state, and being creative with less resources. While she shares some of her inspirations and processes, she exposes the importance of working with non-binary perspectives and challenging what we consider real.

Laila is currently in the final year of her masters degree in Fine Art at Slade School of Art. Recently, her work was shown in ‘Healthy Pink’ with Louis Blue Newby at Springseason London.

On your Instagram page, you often depict your body in constant mutation: being it by using unusual perspectives or by adding body props. When did you start exploring your body as a means to express your ideas?

I think that the idea of the mutating body has always been important. If it wasn't so visually obvious, as is the case at the moment, it has always been something that lingers in my mind — in my research or informing my ideas. I started exploring my own body in this way about a year/a year and a half ago? I didn't have a studio space at the time, so I started to experiment with documenting my own body (which happened to be most readily available) using my iPhone. There's probably something in that process about changing/morphing that which is most familiar to you, into a form which momentarily feels somehow alien.

Would you say that your page @helloo0o0o0oo0oo0oooo00o00o0o also works as a studio space for you then, as a platform to showcase your research and experiments?

I don't think it functions as a studio space, but I'd agree with you in that I use it to share research images and things that I've been doing, in addition to all the other (not art-related) internet debris that goes on there. Instagram feels like a space where I can quickly upload/share small fragments of the things that I make, but the way I use the platform always shifts. It has also just really changed as a platform, especially given their newly introduced really harsh terms and conditions, censorship of content, changes in the algorithm, etc. I'm not even sure if those images of the mutating bodies that you're referring to even feel like artwork, they live on that specific platform and as a result feel somehow disjointed from the rest of my work… although there is an overlap in ideas.

A lot of your work presents images that are difficult to identify as one thing, or that sometimes look like creatures from another world. How do you see the images you create in relation to our current image culture, being increasingly manipulated by AI tools? Is your work any less real than what is already circulating online?

I’ve been thinking a lot about imaging technologies recently, be it the highest resolution video camera, the iPhone, 360 video technologies, 3D rendering, image-generating neural networks… The list is so extensive. With our current digital image culture, I feel like there’s a sense of slipperiness created through processes of image documentation and subsequent mediation, whereby that which is documented is somehow altered or changed by the technology that is used to capture it — things become elastic.

Healthy Pink, in collaboration with Louis Blue Newby (2020) Springseason London. Photography by Gillies Adamson Semple

Manipulation becomes possible through these processes of image capture, maybe once something becomes an image it enables that thing to be manipulated. It's important to acknowledge that this disembodying can be really harmful. I'm especially thinking about the violence (especially misogynistic violence) that can be inflicted on a body that, as an image, is no longer concrete.

There’s quite an interesting relationship between images and manipulation that isn’t restricted to current AI technologies (which in themselves have so many different applications) , or even to the digital. We see it in face-tuning, photographic retouching for advertising, in the historical doctoring of analogue photographs to fulfil a political agenda (e.g in Stalin’s USSR where historical figures would frequently be erased from photographs). I’ve just been looking into 19th century ectoplasm photographs whereby of spirit mediums would be photographed supposedly showing amorphous, ooze-like physical traces of spirits or ghosts spilling out from their bodily orifices (usually the mouth or nose). In this case, I think photography was also used to give validity to the paranormal, providing some sort of concrete proof of the unfathomable. In a broader sense, we've seen this relationship between manipulation and the digital when thinking about things like Cambridge Analytica. It’s not so much about my work being ‘less real’, but exploring how the ‘real’ itself is thrust into uncertainty or perverted.

Air Max '97- Mirrored Gate official music video (2018) Digital video still. Duration 00.04.26

There is also a scientific approach to the way you create and install your works — quite often in your installations, there are very moldable images and materials being held or stretched by metal and acrylic, creating a certain ‘laboratory’ environment. Is science something that motivates your practice?

My mum's a doctor so I used to spend a lot of time when I was a child looking through her medical encyclopaedias. I liked looking at documentation photos of injuries and diseases, and I still do. If it was possible, I’d love to see x-ray scans or the medical examination instruments in her clinic. I’m drawn to the environment of a clinic, with its medical apparatus and furniture, as a space for forensic examination of the body. When I was younger I couldn’t really articulate why this was, but the curiosity was there. Maybe this is to do with a strange fusing of the visceral and clinical, i.e. cold surgical steel or a freshly worn pair of powdered latex gloves placed in conjunction to the messiness, wetness and warmth of our bodies.

So the scientific aspect definitely plays a part! Materially, I feel this is really relevant when considering the materials that I enjoy using in my work. Latex, in addition to its use within fetishwear, feels totally in line with this as a material that is used in conjunction with the body— surgical gloves, condoms, etc. I’ve also been trying to approach video and image in a forensic way… It makes me think of an older video work I made where I used an endoscopy camera to capture footage with, or more recently a macro lens which offers an extremely close-up view of the filmed subject, evoking a microscopic viewpoint. Again, I think what interests me here is the tension created in juxtaposition of the visceral and clinical.

Your work seems to have a very dual quality, being it materially, or conceptually — images that repulse and attract simultaneously, soft and hard materials, the abstract and figurative, history and fiction... What is it about this borderline space that attracts you?

There's something inherently transformative about liminality, the rejection of a binary structure enables something new to emerge. It's not a case of one or the other, but the blending of two opposites becomes a transformative act. The repulsion/attraction boundary is something I think about a lot… It makes you do a double take… it creates what can sometimes be quite an intense experience for someone encountering the work, fueled by the moment of tension that is generated as opposing forces collide. I say 'experience' here because I'd like to think that it goes beyond simply looking at something. The visual aspect is there, of course, but it can set off deeper, more carnal sensations— to feel an image on the surface of your skin, to generate a visceral response within your body.

LAILA MAJID

interview PIETRA GALLI

What to read next