Meena Hasan

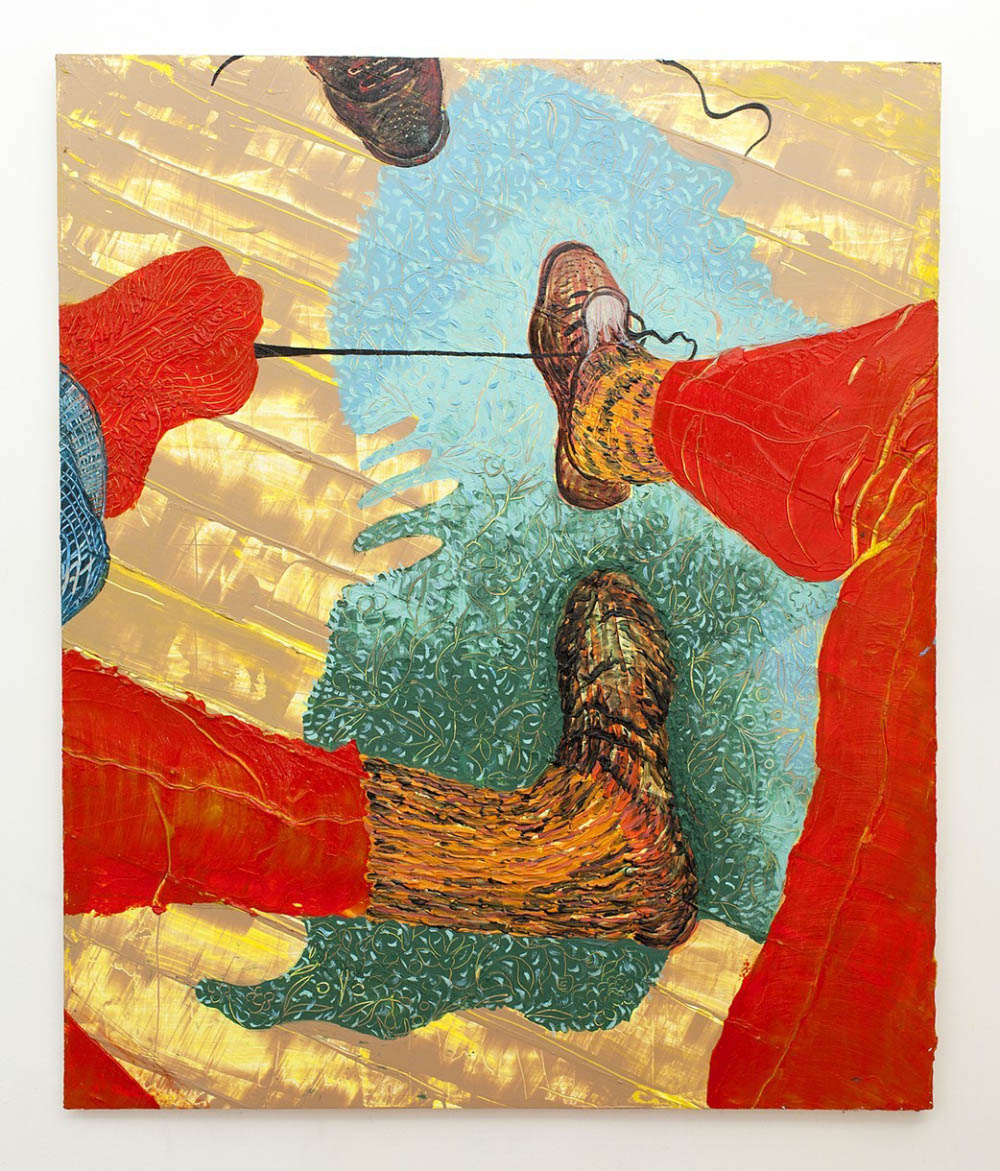

Kati's Reeboks, 2016, acrylic, fabric dye and Okawara paperoverall, 10 x 17 x 6 inches

Artist Meena Hasan was born in 1987 and received her MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Yale School of Art in 2013. Much of her work deals with object-hood and a distancing from familiar contextualizations of such objects. Hasan’s works focus on intimate details and pay a great deal attention and intention to the type of materials used.

She has won numerous awards including the Carol Schlosberg Memorial Prize for Painting and the Terna Prize Affiliated Fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. Her works have been exhibited internationally in group exhibitions in the Netherlands, Italy, and more. She is currently based in Brooklyn, NY.

A lot of your work is on very specific types of paper, such as jute, “handmade Indian Khadi paper” or “Japanese Okawara paper”, is there particular significance to both using these and making sure they are named as the material?

I respond to the specificity of a material, choosing them based on their distinct texture, flexibility and absorbency. Each of my pieces consists of a constellation of different materials, marks and processes. It is important to me to name each element that goes into the making of a work since it is in that fundamental structure that the piece’s DNA is created: the materials, particularly the surfaces, determine the work’s ultimate form and physicality.

I was born and raised in NYC with regular and frequent trips to Dhaka, Bangladesh where my family is from. There is a beautiful abundance of paper in Dhaka and I got into the habit of collecting hand-made paper on each visit. Jute, one of Bangladesh’s main exports, is a common material for paper and its hardness and natural color offer a textured, organic surface that compliments color and line.

Installation view, Meena Hasan and Cal Siegel - wallflower frieze, 6BASE, Bronx, NY, 2017

I study the textile traditions of Bangladesh, particularly Indigo dying and vegetable dying. I often look for paper that shares an affinity with fabric. The handmade Indian Khadi paper is made from recycled cotton rag. Its thickness and soft layers allow me to stain the surface with color or load it up with layers of acrylic paint until it reaches a quality similar to leather or skin. I can even cut into the surface, peeling away layers of paper to erase and sharpen boundaries between textures.

The Okawara is a Japanese kuzo paper that, although very thin, consists of layers of fiber that hold paint like a tattoo holds ink just under the surface of skin. It is an exceptionally durable surface, allowing me to challenge its shape, to crumple it up into a ball, submerge it in dye and unfold it without damage. I can use the Okawara paper sculpturally, letting light pass through it in areas to reveal its thin, collagen-like character. The 3D paper clothingpieces are made with only Japanese Okawara paper and acrylic paint.

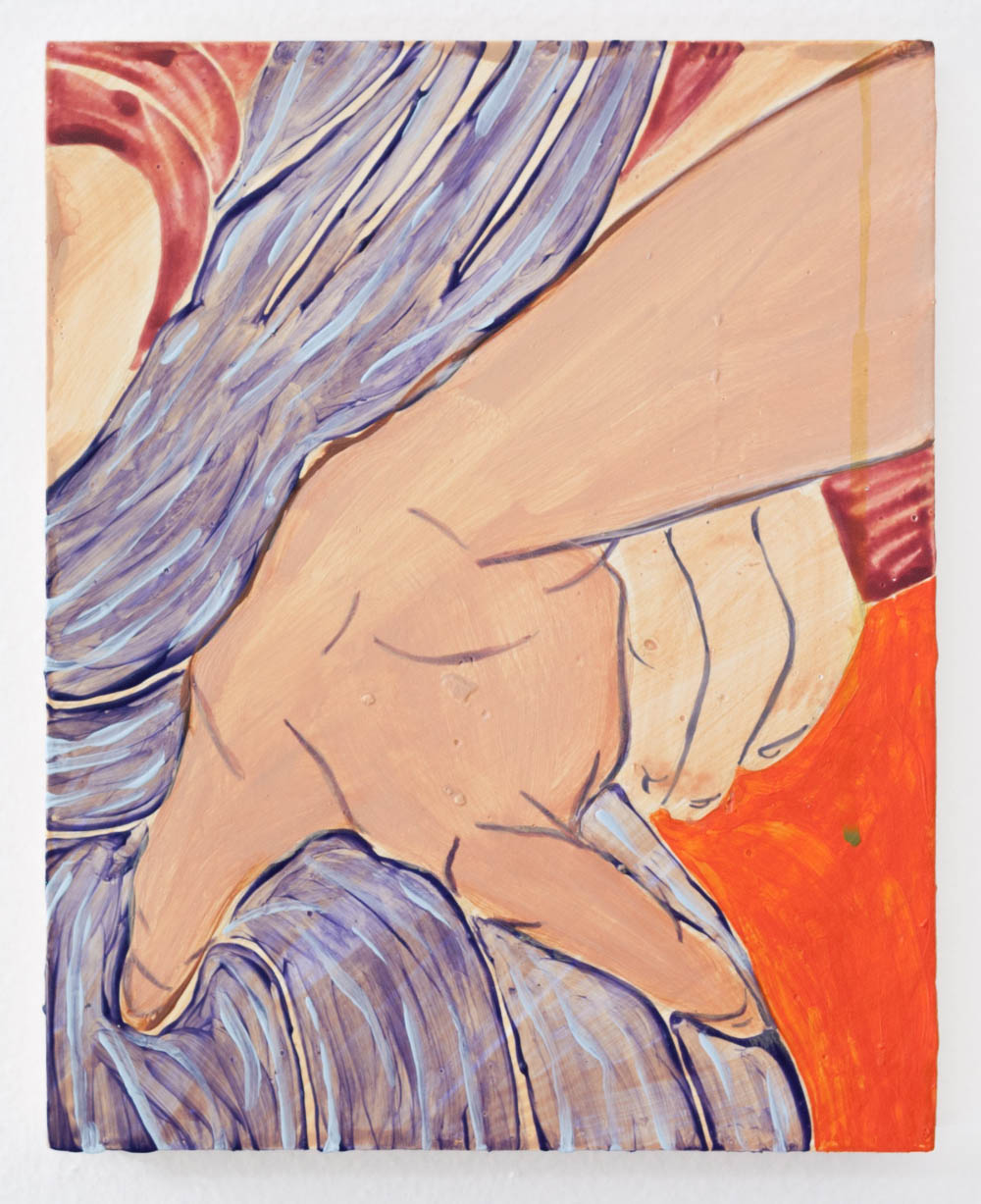

Nape (Violet at the Gowanus Canal), 2015, acrylic on handmade Indian Khadi paper, 37 x 53 inches

Your paintings focus in on and magnify details of overlooked things or the everyday such as “Napes” or “Walking in the Snow” almost disassociating us and creating an enchanting sense of defamiliarization. Can you expound upon this fascination with such details and the specific cropping and magnification?

I hope for my paintings to create an intimate exchange with the viewer where he or she fluctuates between being the subject of the work, the viewer and the artist. In deconstructing and understanding the paintings’ compositions and processes, I ask the viewer to imagine their own body within another’s. Using everyday universal actions like tying your shoelaces encourages this connection and exchange: the images are familiar yet strange and demand a renegotiation.

Walking in the Snow is part of my Point of View series that uses a first person perspective. I started this series after studying the Impressionist drawings and paintings that Bonnard and Degas did of women in the bathroom. These works are intimate peeks into a most private, secret moment (like drying your hair after a bath). I was struck by how the women in these works seem so powerless next to the voyeuristic gaze of the artist: their heads are covered, backs are turned and never is the gaze returned. I wanted to make equally intimate and revealing paintings, but different in that my works give autonomy and power to the subject herself through a first-person perspective complicating the gaze and viewing experience of the work.

I believe that the act of looking at an artwork and scanning a surface for meaning reveals our inherent desire for connection and I strive to set up a subjective viewing experience where encountering the paintings is like encountering another person in the world. In both the Napes and the PoVs I hope to depict strong, singular, subjective perspectives that are dependent on the viewer. So, although the compositions are singular, they are also inherently social in that they are made to be looked at: they implicate the viewer because of their first-person perspectives and their zoomed-in presences.

Your clothing pieces are fantastic, what is the particular intention and/or significance of using such materials to create these objects, yet again evoking this defamiliarization, but in a much different sense of the word?

I think of the clothing pieces as three-dimensional paintings that linger between still life representation and portraiture. I am interested in an article of clothing’s ability to reveal its owner’s personality, history and movements, in other words a clothing object’s capacity to store memory. The clothing that inspires the pieces are sometimes my own, often things I own that have been given or loaned to me by others. I also ask friends and colleagues to share articles of clothing with me that they identify strongly with. I make a habit of this during exhibitions, commemorating a show with pieces that represent all of the artists involved, adding a collaborative element to the work.

The pieces stay close to their original inspiration, creating an uncanny defamiliarization of a familiar object. The process begins with simple still-life drawings of the clothing and these drawings then undergo a dying procedure akin to Batik. The ultimate form of the piece is determined by how the individual drawings fit together, resulting in cracks and crevices that shape themselves based on varied forms of pressure: gravity, brushed paint and soaked water.

The clothing pieces happen concurrently with the paintings and drawings. They give me the opportunity to break out of the rectangular picture plane while still making a painting on paper. The viewer relates to the pieces on a one-to-one scale where the objects’ three-dimensionality exists in the viewer’s reality. The shoe pieces are my favorite of the clothing pieces since they so clearly and humorously articulate the idea of putting yourself in someone else’s shoes. The shoes, like Van Gogh’s paintings of his own heavily worn boots, are representations of people. I examine shoes based on where their soles are worn, where the owner carries the weight of gravity on their body, and all the marks and material the shoe accumulates over time. I hope for my pieces to draw attention to these elements, enhancing our perception of our own bodies’ movements through space.

Sweatshirt, 2014, Acrylic, Ink and Fabric Dye on Paper

Shoes, 2014, acrylic, ink, fabric dye and Tyvek paper on Japanese Okawara paper, 20" x 15"

Given that much of your practice showcases different textures and surfaces, are there any specific textures that inspire you?

I hope for my paintings to draw attention to our material world, to the textures around us and those that we choose to use on our own bodies to mediate our interactions with the world. I am sensitive to how our material reality shifts according to things like our geographic location or the seasons, where thin summery cotton is replaced with soft autumnal cashmere for example.

There are a few textile traditions I look to for inspiration. In addition to the vegetable dying and Batiking I mentioned above, I also look to Bangladesh’s tradition of Jamdani weaving. Jamdani is a thin muslin that one wraps around their body as a saree to create a shimmer of color and pattern that seems barely affected by gravity. The thinness of the Jamdani combined with its layering creates an effect of depth through light and shallow space. I try to borrow that idea of transparency, weight and close relationship to the body in my work. I am interested in the folds in fabric and how they can reflect the folds within our own body and in society around us. These folds create and compress space according to a physical proximity to a person’s body, storing information and memory of the body’s form, movements and emotions.

Repeating forms, like draped fabric, appear in my work often. I speak to an idea of the everyday as repetitive ritual, creating a contemplative space for spirituality and disassociation, further encouraging exchange with the viewer. I often look to Islamic decorative arts, particularly tile-work, for inspiration. I am interested in how my individual touch can mediate the complex forms in geometric patterning.

Raincoat, 2014, acrylic, ink and fabric dye on Japanese Okawara paper, 48" x 30"

Images courtesy of the artist Meena Hasan

www.meenahasan.com

interview PERWANA NAZIF

What to read next