Noura Tafeche

Noura Tafeche is a visual artist and independent scholar whose work and research analyses online culture aesthetics such as sexualization and hyper-cuteness visual trends inhabiting social media and influencing what she calls the rise of digital militarism. Tafeche draws from post-human and critical studies aiming at hybridisation with a strong influence from net.art and radical humor. She’s recently taken part into the Berlinese conference “ARTIVISM. The Art of Subverting Power”, Twiza Festival in Milan, and the “Violence & Visibility in Computational Regimes” conference in Rome.

You define yourself as an independent scholar. I find this definition bold and necessary in the world we live in nowadays, where research is turned into a luxury and institutional monetization at the expense of free knowledge formation and multiversity. What does it mean to you to be an independent scholar and visual artist?

Independence comes over time; at the beginning of my career I was not independent, but simply alone, and I understood the difference gradually. As experiences went by what cemented was the ability not to submit to or negotiate pacts that went in favor of a diminished version of myself.

An example: at the beginning of my journey, not only did I not see a penny I also believed I did not deserve it because I was living in the false Italian myth that convinces you that the work of the artist is vain, and makes you feel like a capricious accessory living off the backs of society.

Over the course of a few years of intense sacrifice (but coupled with dogged determination), I feel that I have taken union control of my work. This, too, makes me feel that the independent suffix has its own pedagogical significance.

What I gradually wish to affirm and if possible, also demonstrate with my experience is that one can make a living from this profession, and be able to say it without emphasis or discounting, so that this becomes a sustainable prospect not for a select few with a well-stocked account or in the red from debts made to pay for a prestigious education, but for a growing plethora of minds who feel the vocation, need, inspiration to want to say something meaningful, without asking permission of how to follow the protocol of approving its validity, from the hegemonic institution on duty.

I distrust a particular section of academia that often parasites on artists' ideas and initiatives by turning our conceptual work into free manpower for theory fairs.

To be an independent artist and researcher means to take it upon oneself to convey a realism relevant to what one lives and not to create the illusions of a crazy existence made up of enviable lifestyles, conferment of status, and prosperity achieved thanks to an intellectual vision that straddles the incomprehensible and the superior, something that in any case only creates revulsion and nerves in those who witness it.

We would not then be so far from the artificial aristocratic and pyramidal worldview from which we feel, in words, so distant. Independent to me also means weakening prejudices.

I think it's important to show a vision of the artist far from easy blunders, sensationalism and hype, because then these frames only serve the purpose of turning into unfulfilled promises that legitimize that preconception of the artist's life as necessarily rambling, unstable and romantically unruly.

And this preconception is detrimental to anyone who wishes to pursue this path. The work ethic in the contemporary art world in Italy is struggling to establish itself, and there are still many harmful practices that the academic world also contributes to reinforce, for example : underpaying or not paying at all, which then turns the profession either into a third sector or blackmail of an alleged curricular prestige, a parameter that at the beginning of a career is often difficult to recognize as what it actually is : a deception. These are real deterrents to the survival of professional categories such as the artist.

Fortunately, the connection of a community of artists helps us to support each other, to give us advice, to unveil those secrets related to accessing our profession.It has taken years to get there, and I hope that this new habit will help to make everything we aspire to build increasingly fair, solid and less subject to threat.

What's your research focus and what method is informing your practice?

In particular, I am involved in research within niches in digital subcultures, a project on onomaturgia (the art of coining new terms), and participatory art projects, all from an experimental perspective. That is to say, little that I do follows a pre-packaged or already broken-in method, usually depending on what I wish to investigate, I hybridize and invent methods that turn into praxis.

The workshop form is the relational expedient so that each individual piece of my research, including the method and ethics with which I approach it, is shared and made visible.

This is not because of the naïve view that we can all be artists (also for the reasons listed above), but more because I believe in participatory processes that allow more people to take ownership of constructive methods for something to come of it, or to just give us less occasion to complain about a lack of tools within common reach.

Again, I am a proponent of the idea that making available, sharing, and discussing unconventional or experimental methods of research, in my view, is crucial so that we do not make ourselves thinned and disciplined in the meshes of elitism, which would otherwise turn the artist to “a classist with talent”.

Net.art and radical humor: how do these dimensions merge in your work?

Net.art and radical humor are a combination that has served as a light in my artistic guidance and that is what I learned from attending the Influencers festival (active from 2004-2019) a place of non-academic training and which I believe has been my real school.

In that environment I came into close contact with the meaning and practice of examples of grassroots movements, media hoaxing, political pranks, hacking practices, culture jamming that were finally considered as a radical and even popular art form.

A sense of humor is something I don't always have the ability to bring out wisely in my work because much of what I talk about deals with issues that are too serious to be treated with a flair that can easily be misrepresented as lighthearted recklessness or dangerous inability to know how to handle disaster.

Lately I also struggle to discern wit in the digital and political circles I frequent, partly because of the large amount of white noise that passes itself off as humor and is instead the perfect copy of that classic nihilistic, cynical and destructive post-irony that emerges as an indecipherable response in defense or attack to an aberrant social reality.

Online culture aesthetics are cornerstones of your research work. Could you talk about your current focus on the sexualization and hyper-cuteness visual trends inhabiting social media and influencing what you call the rise of digital militarism?

My research starts from a sensitivity to everything that possesses characteristics of tenderness.

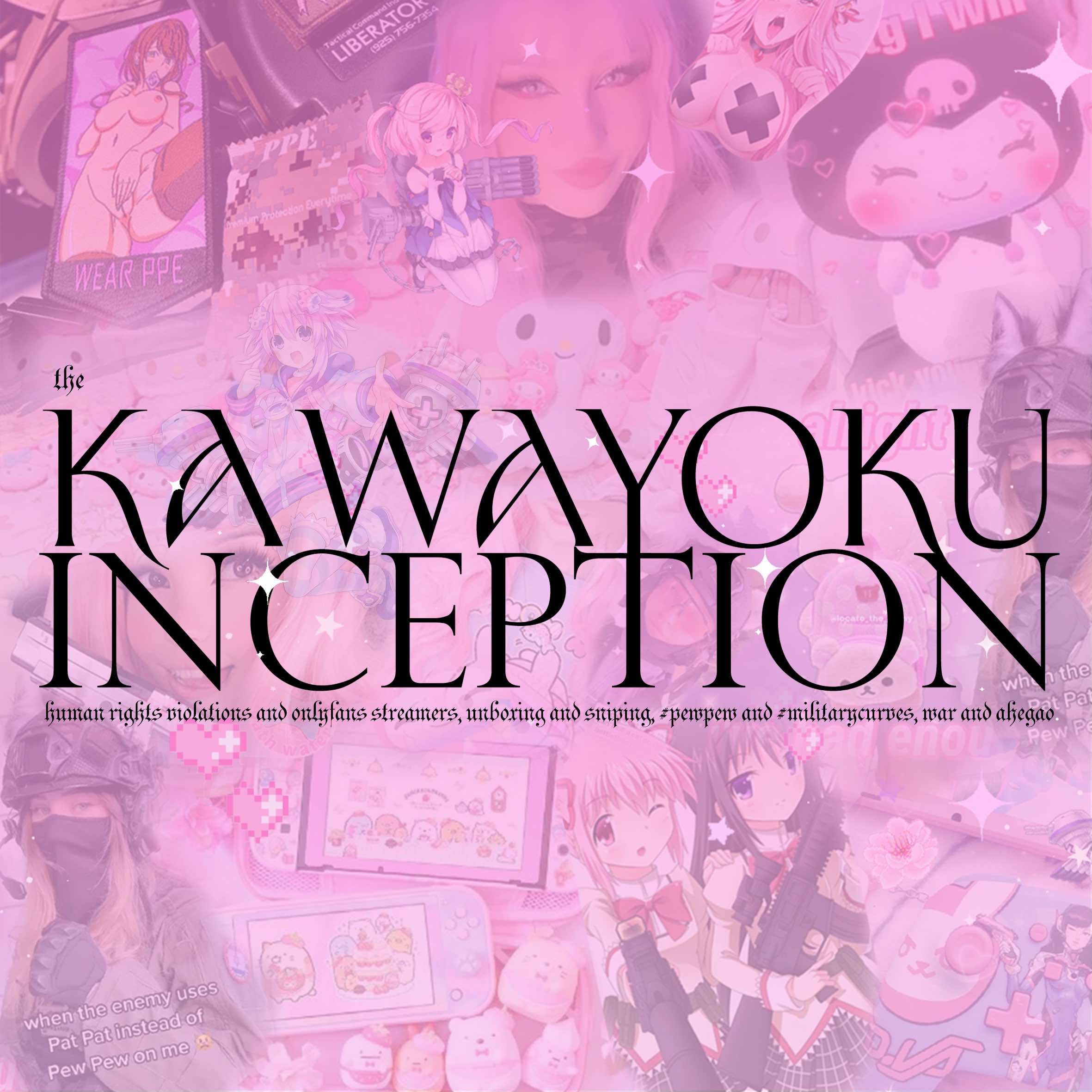

The project we refer to is "The Kawayoku Inception," an archival and documentation work that deals with the topic of digital militarism, aestheticization of violence on digital platforms through the lens of cuteness, the first glimpses of online horror I stocked in 2020.

In 2021 I wrote an article for the international platform Futuress (but not published until 2023) which became the warp and weft of the entire project and an insight that later unfortunately came true.

My text predates by a couple of years what then became a topic that I am now happy to note has come under several radars, though not yet brought together under the same lens, from journalism to research to art to social commentary.

In any case, I didn’t rediscovered the wheel, what I analyze deals with an ancient phenomenon-which I distinguish from the meaning of universal (i.e., the aesthetic desirability of propaganda but adapted to the digital moment), only transmuted in the form of gamification of military aspiration, through the repeated decorative objectification of the female body and moe anthropomorphization that is now the semiotic, aesthetic, existential, and purifying agent of horror that captures the contemporary zeitgeist very well.

The movement related to the kawaii-fication of violence, then, includes not only the presence of armies on platforms and the direct exaltation of war culture (thus the utmost representation of the exaggerated idea of domination and coercion) but a much broader spectrum that radiates across an imaginary that legitimizes misogynistic, supremacist, racist, ultra-conservative free expression and other emerging neo-ideologies whose names we do not yet know.

In addition, what I think is important to analyze is the stimulus that is triggered in the correlation between one TikTok video and another.

Think of the speed of succession with which we can move from one piece of content to another by enjoying its diversification : from cooking recipes for stuffed sandwiches, to NPC impersonations, to live documentation of an attack in Iraq. I'm not talking so much about the content, it happens, it's the Internet, but precisely its rapidity of alternation.

I happened to stumble upon a nail art tutorial, later witness the decapitation of a chicken, and land back on any innocuous trend.

How can we semiotically differentiate between tenderness and violence in the digital space, where the visual representation of the two is increasingly hybridizing, and which in an increasingly accelerated manner alternate and juxtapose as if there is no need for a minimum distance between the two?

Not only such representations to be the subject of the research but the consequences of that provoke i.e., how the imaginative reformulation of violence traversed through the lens of cuteness allows for the dissociation of perceptions of violence as we used to process them, and how and the repercussions of rhetorical and aesthetic power online interact on the offline world.

Is a TikTok choreographed dance by an armed female soldier along a border line to be considered a simple act of entertainment in the ordinary routine in the life of a young private or an attractive lure to persuade her to pursue a virtuous career in the military in the service of yet another "export democracy" operation?

Is this digital militarism inscribed into a particular geopolitical territory or is it a kind of universal tendency toward the aestheticization of death and the anesthetization of senses, thus life?

I speak as an artist.

Digital militarism like traditional militarism has a very high cost to maintain and can be sustained by societies that can afford to prolong its duration and effect, since they can leverage a process of normalization of war culture already inscribed in the meshes of its social network.

These countries are, in particular, Israel and the United States, and they are the two armies I have chosen to analyze most since they were the first in the world to land on digital platforms (U.S. Army joined the YouTube platform in 2006 while Israeli Defense Forces in 2008.)

Yet on this side of the river, the one I am speaking to you from, digital militarism is still little talked about.

It is not just a matter of examining the verified profiles of armies and government organizations on platforms run by Generation Z traction and pretending it is okay, (places by the way teeming with virtual recruiters and warfare influencers), but of identifying how the aesthetic extensions of the army, ergo, its soldiers interact and produce imagery and cultural force and how they can influence social and historical processes by playing with a personalization of a subjective narrative as they have never done before.

Some of the micro Tik Tok celebrities who became more as a result of bombings that their military carried out, play on the ambiguous veracity of their figure: are they soldiers and female soldiers enlisted for real? Since when and how long will they still be? Or are they experimental cells implanted by the military itself?

Are they paid by a communications strategy department? Are they diy influencers with particularly pronounced chauvinistic intentions? Yet there is not only the case of armies that inhabit the feeds of various social media but also of obscure circles such as 4chan threads and public telegram channels that virtually anonymously forage memetic proliferation that promote through anime aesthetics rape culture.

Do we underestimate their violent expressions just because they are on the fringes of the radicalized micro-niche of the Internet? Is it because they are covered by anonymity that we struggle to imagine a definition of their person in our minds? How can we understand who or what we are dealing with? It is getting just harder to learn what is real and what is not on the internet. It is problematic that the answers to questions of such significant bearing are obscure. And it is alarming that whatever we are left with is to be delegated to speculative capacity.

Another worrisome factor, in my opinion is that there is not a sufficient slice of professionals (or even better a network of professionals even with different backgrounds united in purpose) who would co-participate in answering any of these questions on an ongoing and regular basis, like a permanent observatory, existing not only when the casus belli of the digital moment arises or when the hype ends.

In my opinion we still tend to exclude too easily the phenomena, and the very TikTok micro-celebrities that escape the radar and interest of. Because the little talk about them leads one to think that the various phenomenologies are just isolated cases destined to be buried in our memory. One of the many unknowns is what real impact will they have on long-term historical processes, internalized perceptions and aesthetics, individual decision-making abilities, and the collective imagination?

To get a sharper answer, I am afraid we will have to wait for the test of time.

This is where some of my work stops, or at the very least, extends its potential as journalists, researchers and other artists come to create new and ongoing literacy about issues and processes that remain hidden, that tickle only the taste buds of a few, and that sooner or later may be dangerously forgotten.

interview ILARIA SPONDA

What to read next