Tony Oursler

Forever curious about society at large and how our belief systems manifests and embodies creative expressions, Oursler lives in a constant speculative universe of his own. Trying to find meaning in the meaningless world, his explorations on subjects of new media, mysticism, mysteries, the internet and even mental health makes him a unique conceptual artists of our times who’s act is to involve audience as the subject it self.

J: Im curious about your childhood and the following phase, How exactly art was something that called you and how conceptual art specifically was something that you found self doing?

T: Since the beginning i was curious about art and was open for it because of my relatives. I had a great aunt who was a wonderful artist and teacher. She taught grade school in New Jersey. Zeta Mellon was her name. She had a big effect on me, and so did my mom, who also was a painter, but never really did much professionally. She had a different tact. And then my dad was also a great storyteller, also loved art, but he was kind of conservative on many levels. And as it turns out that my aunt was a great school teacher. She was also more of an example of what it was like to live an art life. So I think, in that sense, as it is really good for young people to be exposed to the creative process, but not just in history books or big names, Van Gogh and who's this or that? But if you know somebody who's in the neighborhood who's a functioning creative person, artist or designer or of similar interests like that, this is what really had the effect on me. Of course, thank you to the wonderful mentors over the years there were many.

When I was a kid, I worked in a frame shop for a while and two artists who ran the frame shop and they had worked in advertising, besides, they knew many artists through the years, who were friends and they were artists themselves. That kind of atmosphere worked for me. Later, I ended up meeting a wonderful guy, Kaaree Rafoss, who was a painter, a real kind of conceptual painter, who was teaching at Rockland Community College, where I went when I lived in Rockland county for my last year of high school. He kind of was a mentor to me for a year or so, and I kept up with him. I still keep up with him once in a while, but he was the guy who told me I should go to cal arts. And somehow I think it was a turning point in my life. He also is married to a wonderful artist Pat Lay a great dynamic duo.

The fact that I was able to get to Cal arts in the mid 70s was fortuitous. In retrospect I was already thinking conceptually because I was just very open to any kind of process or path to understand how art was made. it’s one thing to think about being an artist, but then it's another thing to think about what kind of art are you going to make? There's so many great artists out there. How can you fit into. Somehow, of course, being at Cal arts, there was a kind of rigorous program of rigorous self reflection that takes place if the art school if it is functioning well. You have to kind of rebuild yourself in many ways and look at your thinking, and it was a great kind of a vortex to be there at Cal arts and be free to think about that. Also, anxiety producing. My interpretation of what conceptual art is that it’s based more on ideas than it is on craft. And so the idea comes first. There was a kind of stale conceptual art in the sense that there was lets say, stripped down versions of it, put on there other conceptual artist like John Baldessari, corporate a lot of humor and color but my generation kind of took a different spin on it. So it was more of an open perspective applied to pop systems and its possibility. Rather than being just completely philosophical and black and white.

J: Your aunt and your family background has to do quite a lot with the way that you were thinking about yourself. Your childhood has been very nourishing yet, What kind of paradigm shift you experienced when CalArts happened to you?

T: Well, this idea that a concept comes first rather than a visual effect or a stylistic approach or like a craft approach, because when I went there, I had this idea. I've often told this to people and I don't even know where it came from, but I thought I had to learn the craft of all the different ages. I had to learn how to do stained glass or how to do photorealistic painting before I could do abstract painting or something like this. I had this idea that it must come from just didactic situations in schools where people, like, when you find a subject, you work your way through the history of the subject and that's how you master the subject. But I took that very literally in art. So I had already been kind of teaching myself about going through the history. I set about learning to paint like an impressionism before I could do some kind of abstract or pop work. I was working my way through the history of painting and did a little sculpture along the way and like that. And of course that was a fantastical auto-didactical teenage thing.

So, when I went to Cal arts, I thought, well, now I'll really be able to get the inside doctrine, because these people are all professionals. So, reading theory, taking classes in performance art, and, you know, the video synthesizer, different things like that just opened up. I was exposed to all sorts of different ways of thinking. And then this loose idea of conceptual art, which can't really be defined. I realized that the important thing is to have a good idea, because a good idea will get you further than having a good technique. So, that was a fresh perspective to think about that and that was something that I kind of followed from there. It also allowed me to make a few leaps.But for my generation, there were other ideas that we wanted to bring in because there was a different perspective in the sense that we were the tv computer generation. And that's a different perspective on popular culture than the old graphical perspective.

J: From the very beginning, your work has been surrounded by the common themes of media and communication, which is very much reflective of the technological development that was happening at that time. Now, this is also pretty evident that you have been a multidisciplinary yet, I see that your work has always had a provocative connotation to it, a psychological ingestation in terms of curiosity that you maybe either wanted the audience to have or maybe You yourself had, and you expressed that. So would you please tell us, what is it that communication through your art means to you personally?

T: Well, that's an interesting question. That changes through time because I've been different people through out my life. As you change, as time goes on and your interests change, I like to sort of keep things fresh for myself in that sense, is that try not to repeat myself too much once I work through an idea and move on to the next group got ideas. I could tell you the themes that I've worked with over time. It starts in the 70s, really. I was curious about kind of breaking down the notion of television into these kind of stories, the distillation of everything in culture could be filtered through this one kind of corporate stream of images and sound and the hypnotic effect of advertisements. The televised kaleidoscope of themes of pop culture was not really trusted by my generation.

We were wondering, there's one story being told, but then there's another story that's kind of hidden, the true story? we were kind of like looking underneath the rocks of popular culture, to see what was really going on behind the scenes, in a sense. So the early videos of mine were like an animated deconstruction of paintings, where I kind of opened up the idea of what was missing for me in painting, Which was that there was no sound and no motion and no language per se, no performance.The camera was an opening up the graphical idea of painting and usurping the television screen for that, in a very personal way, was the beginning. And that led me into the taking images that were made for television that were painted, turning the painting inside out, turning it into a theatrical space, into a pop cultural space. And that without having any conscious intention, this sort of became installation.

This inside out cycle that I was producing, making things to be filmed and then filming them and then putting them in a presentation situation. That really is how I got into what became known as installation art. I fell into that because it was like video art was interesting, but very limited space. I think I never really liked being captured by one form or another, like, oh, you're a video artist. And I'm like, well, no, I'm not a video artist. I'm an artist, and also who knows what this medium is going to be called later. It just became digital and it's computer art, but still people just fighting these boundaries. So the art was always spilling into spaces and then taking in new themes. So every couple of years I would kind of drift into a different obsession or passion.

I thought about in the early eighty s, I was thinking the way science fiction is depicted in movies and television, and then thinking about literary science fiction, which is more philosophical, and then actually interviewing people who claimed to have had the real encounters with ufos and aliens in real life. And these people had a much spookier perspective and a firsthand interaction with aliens. So working with those kind of themes sounded interesting to me. Say, you have Steven Spielberg, or the guy who directed Star wars, George Lucas. How do they hold up against someone who claimed that actually was either abducted or had aliens visit them at night in their bedroom.

And juxtaposing these two versions of reality, which is, in a way, a kind of portrait of what was going on in America at that time. So I would love to dig around that, or with conspiracy theories like, my work Son of Oil, which had to do with a very loose web of conspiracy theories in american culture, having to do with politics and the oil shortage assassins horror, movies, and building that into installations. Jump ahead 10 years I'm starting to think about multiple personality disorder and other subjects in the context of multimedia feedback systems connecting pop, culture psychology, and mass, medium and identity politics. no other words one body of work leads into another, and this is the way I find my way through the world with my art. And with these different themes, I would create an environment to bring an audience in so that they can be part of the dialogue, so they can experience it in different ways through the poetry of language or the poetics of the moving image. And moving around the space is always important in my work, in the sense that this is often a repeated thing. The aphorism there is no artwork without the viewer being in space.

So the work doesn't really exist without people. So I hope to inspire people, when they come into the space or experience the art in any way, to light people up, because artists learn to speak a kind of language that doesn't exist anywhere else except in art. I think we're lucky in the art world, because we can bring anything in cinema, theater, graphics, whatever it might be, sound, and mix it together to inspire people to connect with people. So it's about sharing ideas, to provoke people. As I mentioned before, let's pit a schizophrenic episode with a Steven Spielberg plot and see whats more interesting?

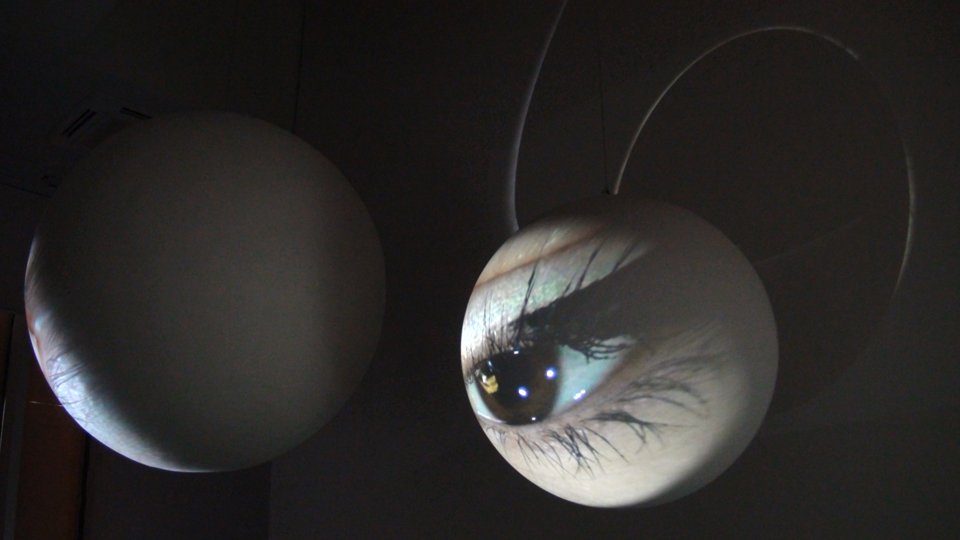

I'm very curious about how sort of free association allows us to come up with new neural links and new ideas. I thought about those installations as kind of chambers that Incubators for ideas, in a sense. And then in the early 90s, some of the pieces were very much more aggressive and mocking. I like the idea, if somebody goes into a space, their preconceptions of what they're going to see in the art world is they're going to come in and see something beautiful that's going to make them feel happy and transcendent, which is wonderful. I love that, and I value that in art, and I think that's an important thing. But I like to sometimes push in another direction. So I thought about having these sculptures, these installations, that would really attack the audience and challenge them, shock them in different ways. And so in the early nineties, when I came up with the projected figures, I thought of them as characters which escaped from film or television space into our physical space. Some would be these very passive aggressive characters. And I had these kind of theories about what attracted people to literature, drama, and art in different ways. They wanted emotions and that they want insights in different ways, and they want energy and passion and so forth empathy towards the human condition. And I was reading a lot about psychology at the time, and so those characters were really meant to provoke almost psychological tests on the audience.

I think I crossed a lot of boundaries, I upset quite a few people because. I think some people, when they hear that. They hear those pieces and they get very angry. They're like, I don't want to hear anything like that in art. I don't want to have be yelled at or I just don’t want to hear it, get it away. But that's okay. I had to do it.

J: I wanted to ask you what kind of challenges you had to face in that time, because not everybody was doing that. Not everybody was taking the challenge to just really provoke the audience the way that you did.

T: Well, that's a really good question. I have a lot of compassion for fellow artists, it’s difficult. Art is one of the few jobs that demands you put their entire heart and soul into the art, and show it to the public to be judged, scrutinized your very essence is made vulnerable through the art to reactions by random strangers. Essentially, it's being a psychological beggar sometimes people can handle that because they're narcissists. Sometimes people crumble and stop making the work, but the average artist has to toughen up one way or another. That's part of the job. No other fields has that many pitfall because there is no right and wrong way and there's also a certain amount of chance involved. In another field if you follow the rules, you'll have a good chance of succeeding. Not so in art. The artist has to take control and responsibility for what they can. I used to tell my students that if you make your work and you have a job that doesn't destroy your soul, you can make enough money to survive and have that time to make your work, you're a success. And that's very hard for artists to accept that that, in fact, is success. There's also this other aspirational side of it, those things can or cannot happen for people, can be very difficult for people to navigate. But I'm lucky because I grew up in a generation where people never expected to make any money from artwork. So I always had a job, whether it was house painting or security guard or whatever, and then I was able to navigate substance abuse and put that behind me, which is a kind of occupational hazard. And then also managed to succeed through the good graces of many wonderful people in the art world who helped me out through the years and gave me exhibitions collected me and took chances on me when I was quite young and this continues.

I had some fascinating opportunities. There was a really interesting network of video. One thing I see now and I didn't see then was in the 70s and early 80s if a young artist made a video it could be sent simply by mail to be in exhibitions all over the world. So for a person who is making our objects this couldn't happen, for a painter, for example. That was Lucky for me and a thrill. And in key cities, San Francisco, L.A, Amsterdam, the Hague, London, Chicago places like that, there was a kind of the support system. But I see what you're getting at in terms of when you're doing something that doesn't really fit into the norms, you can feel it, because, for example, even photography and moving image was put sort of into almost like a kind of its own multimedia ghetto within any kind of museum situation or something like that. And that was irritating or should I say a challenge . And at a certain point I was like, well, if it's moving image, you know, it's never really going to be accepted in the art world. Logically,

I don't really understand why because everybody had televisions and radios in their house and in their car and loved it. I have my theories about why that was, but how they couldn't accept that moving image into the space of painting and sculpture into high art it funny this is happening in NYC a bit now with so much money in the oils there is a back lash. By the mid 1990s I was lucky to see that happen in the get wide acceptance. But there was a moment when I just gave up on the art world in general. It was a good thing for me, I just thought if you just don't think about these kind of structural problems and just focus on the work. I managed to get an amazing job at Mass College of Art in Boston, and I was making just enough to live and not enough to get my own apartment. But I had a roommate and I worked two and a half days a week, three days a week teaching, which was great because I was around interesting young artists and the creative process, and then the rest of the days I could make my work. I thought, well, this is really a success. I can't really ask for more. it was almost like a year zero, philosophically came to peace with the fact that there probably was never going to be the progress in a greater art world in terms of installation and moving image and sound all the stuff I loved and saw as the future.

I still managed to get involved with very cool international projects here and there more in Europe than in the US it's always more conservative here intellectually, but I kept the noise out of your head and to keep focusing on the ideas, which is, I think, incredibly difficult for a young artist these days. It must be incredibly difficult because there's cycling that's happened since that time period. Things have changed so much in the art world. It's not a static beast. It's a growing and morphing situation, more controlled by money. There was no auction world. There was hardly any galleries when I started. And like I said, nobody expected to ever make a living. But also on the good side of it we made the art world huge, thats been a dream to live through that, I think there's just more and more art and more and more interest in art. I think artists have to just continue making the best work they can.

J: I also wanted to get on to your relationship with Mr. Joan Baldessari, what kind of influence he had onto you?

T: Sadly, I never really collaborated with John Baldasari. I tried to once or twice, and I just couldn't get it together at the time, and we sort of planned to do it, but it didn't happen.I have a few artists in my pantheon you know who just stick with me, inspirational figures, like my friend Constance Dejong, and Tony Conrad, Joe Gibbons and John Baldessari and brother Mike Kelly, Jim Shaw, Marnie Weber, people like John Miller, Aura Rosenberg, Erick Beckman, David Askevold Cameron Jamie, Kim Gordon and a large group of younger people and historic figures. And you kind of hold this system in your minds eye who give perspective possibility. Like: what would John Baldasari with this? Rright now I'm sitting here as I'm talking to you, I'm looking at one of his artworks that I have right in front of me. It's a nose with a little phrase below it. It says in a language that is in fragment and just an isolated nose and an image, and it's forever puzzle. And John was just that, he was a very generous guy, and such an incredible artist. His range, the humor, the intellectual brilliance in the work, his kind of foreshadowing of digital culture and appropriation, I think, unparalleled. But John, really, early on, he made a lot of suggestions to me when I was his student, and he personally put me in a lot of exhibitions and connection even when I was a student. He was a man of few words, but the words that he spoke were very precise and informative, some of them I remember to this day.

But also, even towards the end of his life, one of the things about John is that what you know, like people like Picasso, who cycled through different series. Baldassari really did that from the word paintings too the different collage pieces. And towards the end of his life, I went to the last show that he did, and I said to him, john, weren't you getting these images now off the Internet? And he said, yeah, I get them off the Internet now. He looked at me with a focus stare and he said, and I don't even care about the resolution. I laughed so hard, the GOAT! He’s in a wheelchair at the end of his life, and he's still, throwing down the gauntlet. I think we are blessed to have the work it nourishes us, not just our mind, but also our heart and soul.

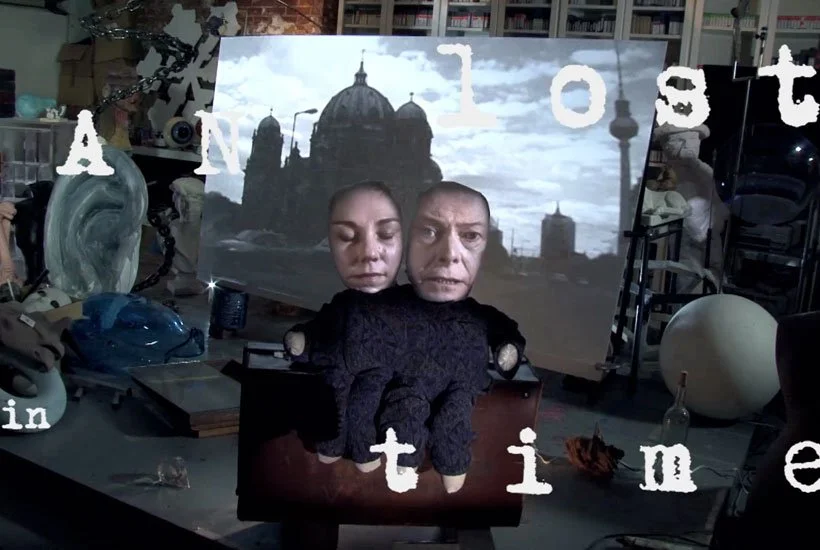

J: Tony,How did you get acquainted with David Bowie with whom you later did the “ where are we now”? I mean, how exactly that happened?

T: Well, I was young my sister Theresa who is also an artist and nurse and i would put on the record, put the headphones on and just listen to the kind of incredible stereo effect, ziggy, stardust, all this kind of stuff— Stevie Wonder. I was always a big fan of Bowie's one way or another. I saw the man who fell to earth in the movie theater, and I had a big poster from that movie. In the mid nineties, I was invited to be in an exhibition in Italy related to fashion, and I saw that Bowie was doing some kind of installation in the exhibition, and I was like, what? I had lost track of what he was up to and, wow, it's incredible this guy never stops growing, never stops trying things out and now he's interested in art. He's going to make installation art, I got a message to him via this exhibition and one thing led to another. Eventually, I got a message on my answering machine, and it was like, hello, Tony, David Bowie here. And he left it on my answering machine. And of course, I played it back for my sisters brother and friends, since we grew up listening to these albums together and loving the guy. For me David Bowie was the ultimate artist because he worked in all, every kind of medium, whether it's film, sound, you name it, he's done it. And also he kind of synthesized it all together into a gesamkunstwerk. I think, in a way, he was always grappling with his roots, as a painter we used to joke about that kind of stuff that no one was ever going to take his painting seriously because he's too well known for something else. But I think for him, the painting problem was the sand in the pearl, something I can relate to.

He loved to be around artists. He came over to the studio, and for me, it was kind of registering this image that, in a sense, I don't know how to really even explain this. Of course, you're not supposed to meet Zeus or something, and they're supposed to be mythical and magical. So then here's this person in my studio who actually also exists on two planes, one on a mythological and one on a human plane. And so it took me a while to kind of register those two Davids. I had done all this work related to multiple personality disorder and popular culture and how that related to identity politics and technology and I always saw David as emblematic of this. A Shapeshifter, who emancipated people by showing possibilities. Anyway, it was really beautiful friendship, and we did projects together and really remained friends through the rest of his life. And that was a really fantastic he was as incredible as you could imagine. I miss him.

J: Tony, What is it you aiming from all this process, What is it you reaching for? As you work looks like a contemporary esoteric ritual, so to speak. But what is it that you personally are trying to achieve?

T :Working my way through various themes, technology and magical thinking recently, I've been kind of interested in certain kind of storytelling. I've brought back narrative, for example, in the imponderable 5D film and archive series, juxtaposition between actual kind of historical evidence and events, and connecting that to artwork, in the sense that the film is an artwork based on reality. And so people can experience the archive, which is historic photographs and objects and books and so forth, related to the story of a battle between, really between belief systems, which is something.

Belief is a theme that's gone through my work to the beginning. Because if you were to talk about conspiracy theories in 1981, while I'm talking about conspiracy theories again today, and those come up with the question of how they function in society and why. And so, there are connections to what happened in the past and what is happening now politically and on the social platforms for example, imponderable. It's a fantastical story which takes place between World War I and World War II, between psychics and magicians and like that.

So there's a kind of the battle there is for people's perspectives, who their gods are, and how they reach them. Who has the power to speak woman had just gotten the vote in this country. That's also something that's echoing now in the political situation today. And that's gone through my work in the past ten years, specifically where I'm addressing our shared history. When you understand that you're in a system, you can think of new opportunities within that system to move forward. And so that's personally, when I recently wrote a long text called Face Wreck, mind control really looked at the history of technology and mind control from the beginning of psychology, really all the way up to the Internet. Those kind of things translate into a project that I'm doing this summer on hypnosis in the History Museum in Geneva, and also a project that I have up now in Florida at the Boca Raton museum, where the Imponderable film and archive is surrounded by some new kind of characters that represent the current culture of mythological characters and magical thinking. But to answer your question, what am I trying to do?

The older I get, I really think the big game is to validate creativity. And art can do that. So on a personal level, I'm able to play with creativity, and I get an immense pleasure out of that, making these connections, making what I hope are new forms that excite people and fire their imagination in different ways, but also to making these kind of interlinking schemata of the world, which is really the way I see it. It's going to be familiar to people when they come and experience my installations but there will also be some surprises unfamiliar territory. It's where you take, there's an alchemy to it. raw material in the old days, it was like paint and color, and it could be found images or sounds in, you know, put together in more complex ways. And, and then when you take these forms and put them together, and people can see that there's another way to do things, you know? Things, just as John Baldasari was kind of telling, saying that resolution isn't something that you have to search for. It's just another palette. The low resolution and the high resolution are just as interesting. It's just how you use them, that the more creative solutions that people can find to things, the better. And I'm not really going to think that art can necessarily solve problems, but it can begin discourse, and who knows what the possibilities are.

And in fact, if you look statistically at what's happening in the world, that's not the vocabulary of the general public. You have, like, 30% of the public doesn't believe in evolution. 60% of the public believes in ghosts. And go on from there. In terms of ufos and aliens, there's a large percentage of the population believes that as well. 5% of the population believes that we didn't land on the moon, things like that. So I think it's important. One of the things for me is that kind of registering the real cosmology, like the real belief systems, has been something that's propelled me in the last ten or 15 years.

J: My question is, what is it that interests you in this? Why you are interested in this common thread of subjects, which is again, to do with now that be extraterrestrial experiences, or it can be about matrix, or it can be maybe, I don't know, mental health or say, spirituality. So, Tony, why do you feel that there is a need to touch such subjects. And why you feel that your art has to definitely touch such subjects.?

T: Well, I think that people are striving to transcend the mundaneity of life, and that's also a function that art can have. So this territory is what makes life interesting for people in different ways. There's a curiosity there of what drives people and what drives the culture, which is something that keeps us all connected. I think that's something that brings us together, and that's what's exciting for me. Although, as you mentioned, as we're talking about, some of this materials are really dark. If you look ahead at what seems to be happening, what the trends are with the new psychedelia, the return to the occult, back to nature, and anti-tech, we're having a resurgence in the new age. And I think that to me, it's something my new work is really concerned with, a kind of disbelief in experts and the traditional education systems and so forth, it’s kind of almost like an alchemy or something. These things happen when the traditional systems fail it can be seen as a historic cycle. And I think this is both dangerous, but also very fascinating and powerful trend like the new religion horizon. But in terms of art, people used to paint cities and landscape to reflect where they live, I'm doing the same thing, but where we live is different at this point. I'm just kind of reflecting the culture I live in the graphic representation of the world is not enough. It never has been since the beginning of memetic technology. Well, my generation is reflecting culture and information in a different way It doesn't have to go through the prism of painting or something that just hangs on the wall. It can go in different ways.

J: With all of your different means of expression, Tony, do you miss anything from the times when technology wasn't this sophisticated the way it is in 2024? As we move towards a more comforting and easy life, What kind of challenges do you go through now?

T: What do I miss? I'm glad to let many things go into the past, certainly television. But what do I miss? I think the promise of the Internet as a kind of utopian space that didn't really happen because it just seems like everything is monetized and limited. I also am very surprised that the negative side of the Internet, which I never would have really imagined was going to happen, because for my generation was like, really? You can publish your own moving image and anybody can watch it on the Internet. This was incredible. I thought this was really going to liberate people from the iron fist of the monopolies of entertainment and the military industrial complex in some way. But it didn't really work out that way new monopolies have come up not even gonna name them here but you know what they are. But what do I miss? Optimism. I wish people could appreciate the moment in which they live. There's so many things that are happening to improve the world technologically culturally it’s a beautiful time that we are living in right now. I think the negativity so prevalent today is just another meta conspiracy theory. I’d adventure to say it's a PSYOP.

J: I'm curious, though, how did your Covid go? How did the lockdown affect you?

T: Well, I live in my mind anyway, and I just really had a good time focusing on writing and planning works. Besides the obviously scary part of it, which was not good to live through, a modern plague. Personally, I wasn't touched in that sense, that I had close friends who died from it. But I was able to write, and I was able to make two really great projects in that time, know. One was this hypnosis project, state non state, what's my friend Pascal Rousseau, which was exhibited in Nance, France. I was able to dip in and out of France between lockdowns. We're showing the project this summer in in the history museum in Geneva so the project still has a life, and it will remain in the collection of the pompidou center. Which is really incredible. I had planned to do this project, a retrospective in Kaohsiung the biggest city in Taiwan. And as Covid kind of came along, it was on and off as you can imagine. Originally I had planned to bring, like, five or six, maybe more people from my team to set the exhibition up. As Covid came along, it first came to Asia, people called me up emailed me one by one saying; I won't be able to go. Obviously, they dropped out. Everyone in the west was horrified of Asia then. As I was sitting in Covid, time went by and I'm looking at the news and communicating with my friends in Taiwan, we were planning on and off as the situation changed. And I'm looking and looking at how people are solving COVID all over the world, and suddenly like a revelation. I noticed something. The whole world has Covid, but there's one place that really has zero cases of COVID and you know where that is? It's Taiwan! My God, the only place clear is Taiwan, maybe we could still do the show. The work had gotten there before covid by boat and it sat there for about a year. NYC was dark and I was staying out in the country and was happy to try to do the show it was a big deal for me we worked a long time on it. Then I got the word from my friends in Taiwan, if you stay in a hotel for two weeks without leaving, you can come here and do this. I'm thinking it's a tropical island, and here it's winter in New York, and over there, it's like sunshine and perhaps even rainbows, so i wish that, please let this work.

So we flew over, with one assistant and then it was interesting because the shoe was on the other foot. In the beginning of COVID, the west was freaked out by anything Asian, sometimes to a horrible degree. But anyway we land in Taiwan, two white guys here, and they were totally, scared of us, pariahs haha we were rushed to the hotel which was very abstract I was fantasizing about floating across the room and falling out the window which was 17 stories up. But we worked on the incredible exhibition catalog, while in the hotel room, connected by computers and phones. Finally, I was able to get out of my room after two weeks, the 7-11 was a vision of extreme beauty! At the museum everybody was super engaged and we made the most beautiful exhibition I've ever done. I'm so grateful to the team there for sticking with me and the project. It is a highlight of my life. I became very good friends with the people at the museum and, to do the show and to be in the middle of COVID to be on an island where there was literally not one case of COVID in Taiwan when I was there. So in a way, it was just like a dream. I have to tell you, Jag, it was very much of a dream experience.

J: Tony, As i saw your work from all these decades, i saw you working manually in places though you are known mostly for your media projection works, but, I stopped myself in 2018 work series, at the predictive empath, which is not to do quite much with you actually experimenting again with technology. You are creating this series by your own manual Hands in here with few painting of rorschach blot bit digital support but, this is almost like a clash to what has happened so far. So, this work which was in Baldwin gallery. Tell me about this, what happened in here?

T: Well, those were an attempt to me wanting to see if I could provoke the viewer to really hallucinate, which is something that I've tried to do a couple of times, but with the Phantasmagoria project in Belgium with these kind of flash psychology tests involving peripheral vision in the installation, which I did there in 2013 Belgium. But the exhibition you're talking about at Baldwin Gallery, I was working with the Rorschach, which, as you probably know, is a psychology test. People tend to see images in abstract patterns it's something the human brain has evolved over long periods of time with obvious benefits. This is celebrated in architecture, with marble split and put together to get the effect of the mirroring stone. So there's this tradition, and obviously, the psychological test kind of provoked this idea of periodolia, where we tend to see images and abstract patterns in our surroundings. And this is something that I've been fascinated by as the way that we're hardwired to kind of hallucinate in certain ways that people don't really even know are hallucinogenic. People associate that with drugs, but I'm not really that interested in taking the drug. I'm more interested in what people can do with their knowledge, imagination and so forth.

Like Salvador Dali said, I don't need LSD. I am LSD. Artwork really does provoke people's imaginations in that way that it can be very profound. I wanted to experiment with this see if I could get people to really see things that weren't there. And it's an ongoing experiment. I'm still making those. I've incorporated mirrors recently into those. So there's a mirror surface, painted and printed surface, and a video surface, and they all kind of combine. It's pushing something that already happens all the time with graphics, with artwork, because you will hear people say, oh, a painting, every time I look at it, it's different. The funny thing is, they attribute that to the artwork, but it’s their brain which is actually different each time they look at it.

J: Tony, I wanted to get onto your exhibition of that time, which is anomalous, which again, touches the subject of unseen mysteries compared to the fairly recent one, the optics and the side effects, which touches on the subject of mysticism or psychoanalysis. So again, my question was this, that you're constantly touching such topics and subjects, which are quite sensitive and quite personal for a lot of people, but at the same time, these are the subjects that people must be comfortable talking about or maybe be okay with knowing specially when its about mental health. As i see, you have a very rational way of putting the subjects out which is may be coming from your curiosity, like you say. So, Are you trying to bring some sort of awareness to people? What you expect to provide to the larger audience?

T: Well, that's a great interlinking of questions there. I love that. Speaking about the facial recognition, which goes to the key of what we were talking about before, which is that the old idea of a portrait of somebody is the skin and the eyes and the hair and the clothing and the setting and so forth. And then you have a portrait of somebody which is photographic or painted or whatever, sculpted as representational. But the portrait today that we living in information age is of somebody not even graphical in that sense. Through facial recognition, you're recognized as a series of numbers, which is a relationship between your features. And in that way, you can identify, like, anybody on the planet. And once you're in that system, that could lead to the aggregation of all the information about you, which becomes the kind of new portrait. What your search histories are, what your buying history is, your medical history, your educational, any kind of information that's on the Internet can be gathered together. Your social media can be scraped and put together, and this can be, as I said, an aggregation of you for example as, Jag. And this is really the new portrait, which is a kind of numerical aggregation of information.

And that series was trying to bring awareness and dialogue to that and voice some kind of poetry around that, and to bring that up as a kind of mutable portrait of the person that's forever changing. And this is the way I get into these different perspectives on what's happening around us. And then when it's exciting, it ends up exciting me and eventually will end up in my artwork. And recently, I've been thinking about this kind of cast of fictitious characters that have been developed over the time. These kind of mythological creatures that come up in pop culture, like Mermaid, alien, the Flatwood monster, kind of rock star projections, the big Cardiff giant, who I've been working on for a couple of years, and fairies and the machine elf, which is an interesting one that comes up through psychedelics recently and kind of interconnecting these in Boca Raton, there's a kind of menagerie of these characters which kind of interrelate. And that's the first step in that project, really, the cast of characters. I guess it's a good bridge to go into some of my outdoor projects. I've used the landscape and reprojected back into it various explorations of cultural histories and moments with the influence machine or tear of the cloud. This has been very exciting, I recently finished a commission in Texas where there's an outdoor projection into of what they call an arroyo, which is a stream that cuts through the wonderful layer of stones and a pool of water and the edges of it, and to construct a kind of composition which can be seen there, which is permanently on display in a sculpture garden. I've been incredibly lucky to have these opportunities. I think it may be the most beautiful thing I've ever made I cried when it was completed.

J: Tony as you have done plethora of work i also wonder the kind of creative direction, or atmospheric direction that maybe you must go through when you are doing the artworks indoor versus outdoors. I mean, how does that affect the way that you want to give experience to the audience?

I've been very lucky to have a chance to work with people who can support my outdoor projects. My friends Jill and Peter Kraus have a major work on their property in upstate New York, that took five years to make that piece. It's interesting thinking about the slower times of past as we discussed earlier. One of the great things about working with the Kraus’s was they had no time limit on when the project had to be done which is so unique. So we did a lot of experimentation in the landscape and with materials. We landed on three spots in the landscape that interacted to form the installation. We projected on a bronze root system, which was taken from the property and cast and put back there to become animated. We project into a stream bed and a large stand of trees. I grew up along the Hudson river, and I always had this kind of reading of the Hudson as a series of interconnected points, which formed a kind of creative energy a flow analogous to the flow of the river which moves in two directions. So much happened along it shores at different times. The beginning of the film industry in the US was along the Hudson valley, on the Palisades. Bell labs developed the first transistor. IBM developed AI. Edgar, Allan Poe developed his poems and detective stories in the area. grandmaster flash and Joseph Cornell. I have a dialogue and connection with the appropriation. I knew the first military academy, West Point, is on the Hudson. I knew that the first american art movement was in the Adirondacks, where the Hudson river began. And so over the years, living in this area on the east coast, I had this kind of mental construction of all these things that happened there. The fact that the telegraph was invented by Samuel Morris, who was an artist and an inventor, was also along the Hudson. And so I kind of linked all these things together, and that project gave me a chance to kind of make this layered exploration of that region as a kind of creative conduit. Almost like that the river was a kind of flow of energy, almost like electricity. So I kind of developed a project around that particular project with the Krauses. It was originally developed through the Public Art Fund with their support and projected along the banks of the Hudson River. I was able to evolve a new perspective on how I could work outdoors, which was silent, there was no sound, and I kind of moved into a more visual exploration, rather than just talking heads. I kind of worked with different gestures and animations and performative elements and so forth, that kind of evolve my outdoor projects in a wonderful way. There are chances to do things that are almost impossible to do to project directly on the Hudson River. For example, was a Highpoint in my life, to do a permanent projection, as much as anything is permanent in this world is unusual. But to work on a canvas, which is actually a landscape, is such an interesting project, and I don't take it lightly. I really see what can be done.

J: I saw the transition from 2022 to 2023, the kind of work that you have done is pretty on similar subjects, again, now that be mermaids, or that be angels and crystals that you have tried to reflect upon, and then you have also used beautiful lighting to kind of express maybe say an outer body experience with smoke and mirrors. What exactly happened? I mean this is something that I feel is completely different than 2021 work series that has come out. This maybe has also something quite to do with after the lockdown effect, that maybe has happened because there was this new age spirituality topics that were kind of on surge as everybody was just talking about this. Again, new age spirituality and psychedelic experiences and ayahuasca. Of course, this entire thing definitely starts with the January and March Future Shock series. And then again from that it goes to the so and so forth, which is machine elf New York. And then teacher Foo Fighter in this book where book has an ario. So what exactly 2023 was all about that now we are into 2024?

T: Well, yeah, I like your perspective there is thinking about. It goes back to this discussion we were beginning before related to the new age and this kind of connects to these mythological characters. And there's a kind of overarching, I think that it has to do with your question of people yearning for this more quiet time and they want to get back into materiality not digitally. We all are scared of climate change, which is very important to me. The ecology is always really important. So I think if you put all these things together, people are disenfranchised by politics, which is right now a very violent and divisive situation. So the new age offers an escape, a new paradigm. And I think of course there's a heavy drug part of that, which, I think is problematic, that to do with escapism, but separating that out. I think there's some interesting parts to it that need to be explored and that's where I'm moving in that direction, which is to think about this new age movement, which it seems that there's also a psychopharma pharmacological part of it, which is that the new promotion of psychedelics by the big pharma is always little bit worrying when I see things like that. But I'm also really curious about it because psychedelics are a way of accessing a kind of an instant revelations as told by the users. And I'm not sure whether that's a good thing or a bad thing, but it's certainly interesting, you know, and it also puts as movements earlier such as spiritualism and things like that, where they put the individual at the center of the universe in the sense that they have a direct connection to the divine, and it's chemical and you can be working at the big box store and instantaneously be with god or be a god. But it's also an interesting phenomenon to look at. So I'm kind of digging around, I thought maybe I should write some kind of a ten point power of positive thinking perspective myself. And I may do that, actually, at some point. You know, the work is that it's not really about giving an answer, it’s opening up these areas of exploration, interrogate the situation from different perspectives, it can provide clarity in tumultuous times.

J: Tony, I wonder about your own personal relationship with such subjects and theories, what is your very own personal relationship with such frameworks?

T: Well, I believe in some higher power, for sure. I like to think that it's a unifying force. And I'm constantly fascinated by the mysteries of life present in hard science these mysteries are as magical as anything that is classified as mysticism or spirituality. Look at the aurora borealis. Even if I’ve only seen it on instagram, I just love it. But my religion is really art. And I really believe that art can bring people together. It's one of the last places in culture where the individual's perspective is valued. And I think that's important to remember, it's different than popular culture in general, if you go to the movies or whatever, it's prescribed, you’re a paying member of something, you're in an economic model.. But when you experience art, it's not about that. It's about what you think. And when you watch a Netflix movie or something like this, no one cares what you think about it, because you're just following the path that they want you to follow. But in art, it's never complete without the viewer. So I think that this is an important position that's unique in the culture. It can also be a kind of creativity engine, that we can find models for creative solutions there, because I think it's transposable, outside of the art world. If we learn to think creatively, it can be used in any way, whether it's engineering or finance or science whatever it might be. The creative engine of humanity, is not limited to the art world, but the art world is definitely an origin point that I'm happy to be in.

J: I was going through many different interviews that you have given Tony, and I'm not sure which interview was that, if I had read it somewhere in the article or if I had watched a video. But you did mention about you experimenting with AR VR and more immersive experiences and expressions. I wonder, what do you think about the metaverse space that has come now from an artistic point of view?Of course. What are you thinking with the future of technology, and how are you really looking forward to kind of blend with it and then go ahead with it?

T: Well, the problem with VR is that it takes a lot of work to develop these kind of projects. Like I've done many Internet projects, CD roms, even VR. I worked with Adobe on a VR museum, I did an uncanny valley project with them. And through the years, I've even done some really fun VR projects, et cetera. And the problem is that they'll become obsolete in four years, three or four years. And then the platform, it's very difficult to keep it going. So for an artist, that's not really practical because you can't really function that way unless it's so simple, you don't spend a lot of time on it, and you're able to keep the assets. This is what I learned: keep the essential elements somehow so they can be used again in a different format otherwise they get locked is an obsolete format.Artists have to future proof there work. I'm part of a beautiful AR project Alpha 60, put together by Michael Levy, up in Boston.. I love that kind of thing because it uses a phone very easily and it's not so complicated to do it, but the effect is very strong. The culture really needs to turn the phone into art desperately. And Micheal is doing that. But practically artists have to future proof themselves and be able to carry the message forward, use it in new platforms. But the problem with something like you mentioned, metaverse, even though I haven't really seen it, it's going to be corporate and it's going to be, you're in somebody else's system, and that's always going to be a a problem, in my opinion. I had a lot of hope for these kind of things, but it really turned out differently. I think you have to be really naïve to believe that technologies being offered up are some kind of Utopia. I'm very curious to see, like, apple has just come up with another set of goggles. good luck to them. We'll see. We might have come to a point where people just don't want that. They're really tired of technology in that sense. Like, they want less technology. They're in front of screens. I forget the statistics, but some people. It's 12 hours a day.

Yeah, absolutely. You're right. And to put goggles on, screens closer on your eyes? it's obviously going to be sports and pornography that are going to be the success of it. And probably there's always a market for that. But I think for me, I don't want my son doing it, and I don't really want it. I don't trust it, even medically. I don't think it's good to have an electrical screen attached to your head. It's a good idea, but in a sense, I sound like a technophobe, but I'm not. I just think, obviously, these systems that are going to be available, they're corporate. They're meant as a way of taking your money. Can art be made in that, maybe great things can be made. But I'm more of an underground type guy.

Goggles, I don't really want it. I don't trust it. Even medically. Many years ago, I remember a lot of these starry eyed techno gurus, talking about VR and I even found out at the time back in the 90s that a lot of this material was being used by the military for simulation. It wasn't really a beautiful future. There was one place in New York in lower Manhattan where you could try on VR glasses. It was the only place that you could really do it, so I took my class there from Cooper Union, and it was really funny because the goggles had to be sterilized and you had to sign a form a waiver related to the germs which could be transmitted through the goggles from person to person. I found that very funny. Today, I don't think it's good to have an electrical screen, like attached to your head. It's a good idea, but in a sense I sound like a technophobe, not. I just think obviously these systems that are going to be available, they're corporate, they're meant as a way of taking your money. And whether that can, art can work in that maybe great things can be made. But I'm more of a gorilla type guy. I like something in the sense. Okay, I'll put this to you, Jag. Right now, the iPhone, which is I guess one of the most popular phones in the world and probably all the other phones, they are already a computer that exceeds by many thousands of times what was used to put people on the moon. Okay. And people have that in their pocket and they're already, I mean, some people are probably making art out of it, but the real problem is it's really a distraction for people and also about kind of capitalism suck.

What I'd like to see is more emphasis on creativity with technology. But I've been saying that for years, it’s a continual struggle, whether it's going to be the destruction of the generation or many generations, or it's going to be the emancipation. I think the jury is out. No one really studied what happened to society when television came in the 1930s and 40’s. I have only been able to find a few studies, people stopped going to dances. They socialize a lot less, they spent time isolated. People probably became less creative, on the other hand, there's going to be some upsides to it. The important thing to understand is that time rushes by quickly with technology no one's really paying attention to the psychological or social aspects to it. You can count on that. How has the smartphone affected the new generation of people? I mean, obviously we're more connected socially. Yet in the usa there have been catastrophic social trends education has suffered, violence increased, drug use. Many I've endeavors are much easier via technology. We are doing an interview across how many thousands of miles, which is pretty cool.

J: It's both Bane and a bune in its own way, for sure. I just wonder, Tony, when you are actually working on many of the different subjects which are of curiosity, psychological curiosity, intellectual in its very core. I would definitely say that. And the recent times, of course, when things are very readily available, I mean, you have to just touch few things and then click some numbers or texts and then things are readily available and information is right there. I wonder, when it comes to your artwork, is there something that you wish that your audience and people coming in, seeing your work, they be prepared for now that you're already pretty known and people are already kind of aware the kind of subjects and areas that you're touching in the larger society. Is there an expectation that you have from the audience when they come in?

T: No. I try to imagine them as ope, there's some cultural references that we share or not, but I try not to make them too obscure. At different points in my life, I've got really interested in historic moments and how they still existed in pop culture today. Things like horror in pre-cinematic image production with the magic lantern and things like that. I would talk to people about it and I see their eyes, like, rolling up in their head. They're like, what is this guy talking about? I was super excited about it but people had a hard time connecting . So I've reined myself in from the insanity of cultural historic black holes, I think. I’ve always try to keep things in the current vernacular. But one of the great things about the Internet today, oddly, is Wikipedia. YouTube, Wikipedia, in the very beginning of the internet were totally unreliable, now when I get into a discussion I'm not sure what year was antibiotics really invented? And you're like, no, just look it up. It's right there on the Internet.

That's something that maybe that's dating myself. But I'm still profoundly impressed with the fact that I was one of those kids where I was like, man, I wish I had the encyclopedia. It was impossible, if somebody had like a really nice encyclopedia something, it could be really a cool window into information. It's also a strange paradox that digital culture has caused an inversion of facts. But generally I see it more and more, certain subjects that I researched like 15-20 years ago that were really obscure such as spiritualism and art. There's massive web presence on that stuff now. I guess my expectation is that people are curious and that they are not afraid to look at things. A lot of the work since really 2000, I mean, for a long time, I kind of dip into deep history and mix it with present time and also to have a notion of some kind of futuristic thing. Just like us the art work has three times at once a palimpsest. So I hope that people are curious, I guess.

T: Yeah, i feel you are on a quest of maybe a psychological experimentation with almost the entire society. What do you feel when you are working on your projects?

J: Yeah, I'm a definitely a closet scientist. I mean, if I had enough money, I would probably be doing some kind of hard science along with art if I could indulge my fantasies,. If I could have a team of researchers, I'd love it. But that's very kind of you to have that perspective. Like I'm some kind of analysis of the whole world, but I'm just having fun, really. I like to explore, and I like to make things, and there's a kind of great pleasure to that for me. Artists are people who commit to making connections and occasionally through the process they get to see things that are somehow beyond their capacity. Its a shared experience we get to stand in the light together.

J: Tony Oursler, the psychologist who's having fun, how does it sound to you? I wonder, this new age culture, Tony, that we have kind of transitioned ourselves into, what kind of subjects and topics that you are thinking to work upon because you have pretty much summed up the social issues and the psychological and the spiritual and even metaphysical. I wonder, what are you really looking forward to do from this point of time?

T: I’m getting to know a new American population, mythical creatures, contemporary mythical creatures. India has a rich history of mythical creatures, and the western world through the Greeks and Hollywood special effects have a great history of these mythical creatures today. There are newer creatures that we talked about before that are being created, Carl Jung talked about that as a way of looking at UFO culture are the new myths. And so that's what I'm kind of interested in because that brings in a lot of these conspiracy theories, which I’m working on as well, which fascinate me because they seem to be connected to the same subject in that people are trying to build new narrative structures and new kind of mythologies around, for better or worse. Its something that I've always been interested in, in the working on what they used to call it urban myths in the 1980s. Such as alligators in the city sewer system, a little bit more humorous and less hardcore than the conspiracy theories today.

I've done some work on the moon hoax conspiracy, and technophobias such as anti 5G. And I'm very curious about. One of the great things about social media is that I kind of subscribe to all fringe feeds which relates to the flat earth and so on I can track them. Obviously, I'm not for flat earth, but. No, I'm fascinated by the mythologies around that and what the purpose of these theories are today and how they function with people. I love the visual, the graphical representation. Generations of artists view the world how it seems important at the time, oil portraits were painted hundreds of years ago and now we have facial recognition and digital footprints, pop artists were really curious about Campbell's soup cans and comic books and things like that, graphics issues of high and low culture on that level. My generation is more interested in social systems and their effects, chemtrails, aliens, machine elves and social media, tracking culture in a different way. So that's where I'm at right now.

interview JAGRATI MAHAVER

What to read next