Vica Pacheco

FIBER and Flemish Arts Centre de Brakke Grond invited Vica Pacheco to create a new performance, which became the starting point for this conversation. Known for her multidisciplinary approach, Pacheco reactivates ancestral technologies through sound, movement, and installation. She builds her own instruments, often inspired by pre-Columbian ceramics, treating clay as both a sonic tool and a vessel of memory. In performance, these objects breathe through water and air, behaving as animate presences that evoke ritual without replicating it. Rather than reconstruct what has been lost, Pacheco imagines new ways of listening and relating to matter. Her practice draws from mythology, anthropology, childhood memories, and dreams, creating sensorial worlds where the invisible becomes audible and the symbolic takes physical form. Silence is as charged as sound, absence as present as gesture. In her commissioned piece, she continued this research by composing a space that invites collective attention and somatic awareness. The performance was not a narrative, but a situation where sound and movement became a form of thought, where the ancient and the invented coexisted as equal forces.

What drew you to working with dancers and light, and how did these elements shape the rhythm at FIBER Festival?

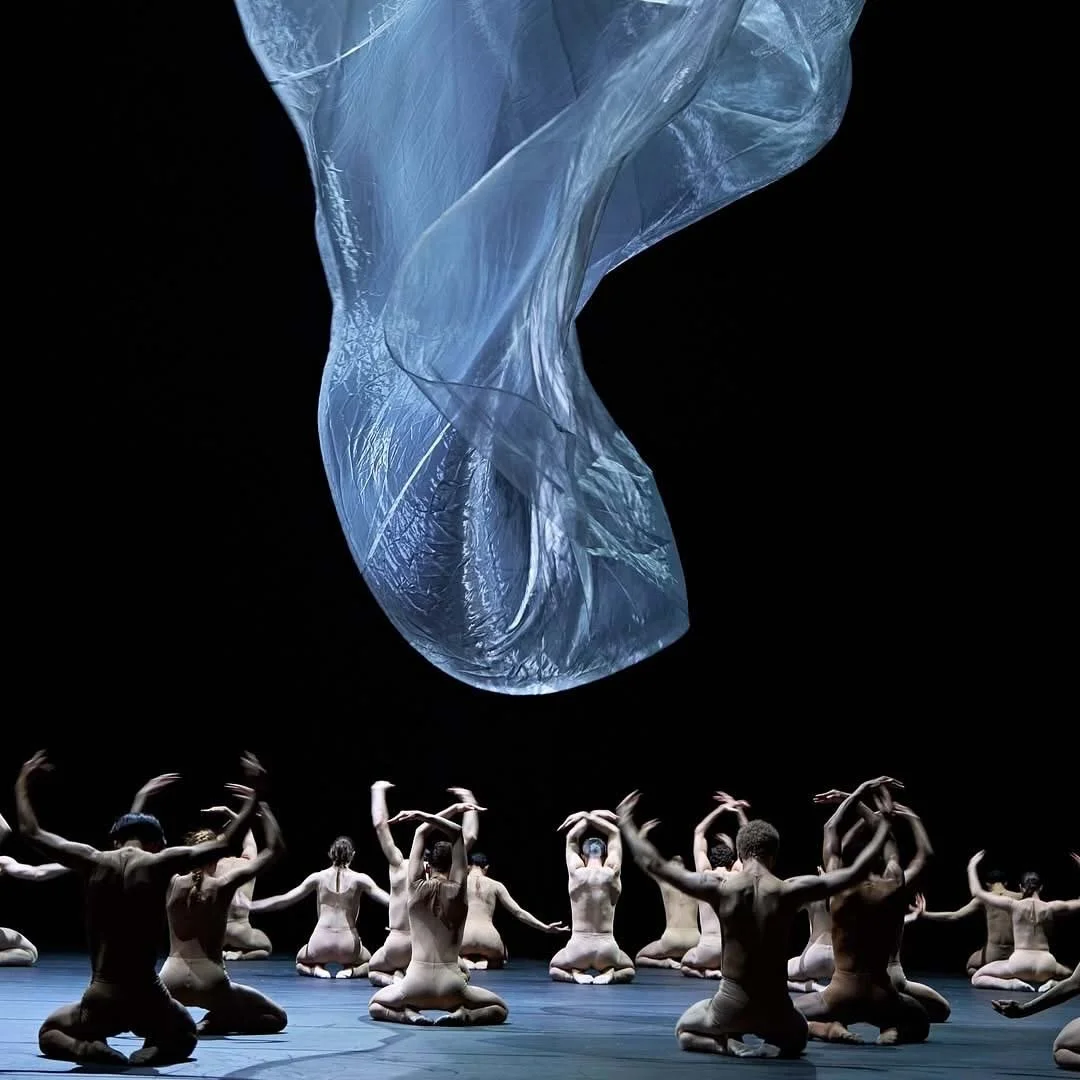

I’ve been working on a really new piece with my three dancer friends: Fernanda, Francesca, and Siet. It’s the first time I invited a light designer Lea Ware, so it feels closer to something like theater. I wouldn’t even know how to name it yet. We’ve only done three showings so far. But I can say it draws from simple gestures, shadow work, and this idea of something obscuring and then revealing, the way an eclipse behaves. There’s a rhythm of hiding and appearing. It is very visual but also abstract.

I kept thinking about Kabuki, even though I’ve never seen a live Kabuki performance. Only videos. It is a fantasy. I’m not trying to recreate it, but its atmosphere inspired me. This piece is also one of the first times I worked with slow, repeating patterns, both in movement and in the transitions between darkness and light. It is minimal, and it relies a lot on contrast. The presence and absence of light become part of the choreography, as do the silences and the unseen elements that you can still hear.

It is a sensorial piece. My voice is present. The instruments, the sound textures, the technology, everything is held together with this personal touch. I used Ableton to process and build layers. In the end I think of it like a black canvas. Sometimes, when you close your eyes, you see flashes of light or color. That is the image I carried while working on it. Small bursts that appear, disappear, and linger in the dark.

You were born in Oaxaca, studied in Mexico City and Nice, and are now based in Brussels. How have these different cultural and geographical contexts informed your artistic language?

There’s a cultural heritage and kind of early education that I carry with me wherever I go. Then there’s my path in art. I started studying in Mexico City, but for personal reasons I moved to Nice. It felt like something led me there. I ended up at Villa Arson, a school known for its open and multidisciplinary approach. You’re encouraged to follow your own direction, as long as it makes sense.

That changed a lot for me. It gave me space to question what kind of artist I wanted to be. In Mexico, art often has a strong political drive, which makes sense given the context. But in France I realised I could also work from other places, ethnography, nature, history. I started experimenting with new mediums, and that shift stayed with me.

Later I moved to Brussels, which brought a different energy. Music and performance are very present there, and I found a sense of community. It became a place where everything came together, what I’d learned in France, what I brought from Mexico. Each city shaped a way of thinking and working that still informs what I do today.

Your work seems to move fluently between sculpture, sound, animation, and performance. How do these forms communicate with each other in your process?

For me, everything begins with sound. It is the element that holds everything together. No matter what form a project takes, whether it is a musical composition, a performance, or something more electronic, sound will always be present. It is how I express emotion and tell stories. Other mediums come in as tools. I learned ceramics along the way, and although I work with it often, I do not call myself a ceramist. Real ceramists are deeply immersed in that craft, always refining their glazes, maintaining their studios, working with precision. I see ceramics more as a material that naturally found its place in my practice.

The same goes for animation. I have loved it since I was very young, after discovering William Kentridge’s work. It struck me as powerful and direct. I have explored other forms of moving image as well, and it has become another tool I return to.

Performance is where everything comes together. It is the space where all these elements start to make sense. I might begin with a sudden idea or a moment of inspiration, then ask myself what it needs. Animation, ceramics, music, movement. Each project decides its own form.

In your recent work, I noticed a recurring use of shadow behind the forms you create. It feels intentional, almost like a presence that follows or doubles the figure. Are you thinking of this as an alter ego, or is it something else?

This idea of the shadow has been with me for a while. I read Jung’s autobiography last year, and it left a strong impression. The shadow is part of us, something we often overlook, but it has its own activity, its own agency.

In Eclipses, the piece you’re referring to, I was thinking about what happens when one body covers another. What do we really see behind that? It connects to what you asked earlier about the audience. I’ve realised I really enjoy this space of ambiguity. It becomes a kind of game. I like when people see my work and respond with something unexpected, something entirely their own. Shadows are perfect for that. You don’t see the object directly, but you still see a figure, a presence. It opens up interpretation without being invasive or didactic.

For example, in this piece with the whistling vessel, it’s made in two parts, moved by two motors, and what you end up noticing is the shadow. That element opens perception in a different way. It offers a small moment of freedom.

You’ve reimagined traditional pre-Hispanic instruments, particularly whistling vessels, through a contemporary lens. What role does animism or spirituality play in your relationship with these objects?

Over the years, my relationship with these instruments has shifted. I’ve been working with them for a while, and the ideas I had in the beginning have naturally evolved. We change, and what we learn changes too. At first, I was fascinated by their form. They reminded me of oars. Not in a literal sense, but as something tied to Latin America, to histories that were erased or not considered musical. During colonisation, many sonic objects were discarded. These instruments became archaeological remains of a world that once sounded very different.

They carry a form of resistance. What makes me trip is that archaeology can only build speculative narratives around them. The cultures that made these objects were silenced. Their iconography was destroyed. These instruments now sit in museums, surrounded by guesswork. But that gap is where I work. That space of interpretation becomes a creative opening. It is historical, emotional, and connected to identity. When I say “us,” I mean Latin America. And I know I’m not the only one drawn to these instruments.

They are like anchors. You can hold on to them, and they offer you a kind of freedom. Other objects from history come with instructions or explanations. But these ones don’t. They are still vague, still unknown. That makes them feel more alive. There are so many interpretations. I’m drawn to the animistic one. When I see a clay body move and make sound, it feels like it’s breathing. That sound is fluid. The water makes it feel alive. Just like blood does in a human body. That creates empathy. You start to relate to the object.

We call the biggest ones “the dragons.” They are filled with water and air. These elements do something. They create a bond. Suddenly it is not just an object. It becomes something you care about. I did not aim to recreate animism. But the connection happens naturally. Over time, these ideas stayed with me. The reinterpretation of history, and the way fluid material creates this strong emotional response. It is not about spirits. It is about the presence of the object.

There is also something powerful in the idea of communication. These instruments were likely used to speak with nature. To imitate birds or animals. That intention feels beautiful to me. I want to continue that. Some of the soundscapes we create still carry those qualities. They sound like birds, like rainfall, like small creatures. I like to think that was part of the original purpose. To feel close to nature. To be in tune with it. That, to me, is a meaningful kind of technology.

“Mitote" and "Animacy or A Breath Manifest" are both pieces that seem to create ecosystems rather than just installations. When you build these worlds, are you thinking about ritual, play, or something else entirely?

I'm thinking about places. I like to create places. Environments. It's more about creating spaces than rituals. Rituals come naturally when we activate bodies or follow certain gestures. But when I talk about installation, like Mitote, I’m talking about creating a space. The ritual is something else. Mitote, just as an installation, comes from an anthropological text I wrote years ago. I was researching why these instruments were used. One reading mentioned a story shared by an old woman in Chile, possibly in the 70s, which makes it even more distant now.

She said that people used to carry these vessels with them when working in the fields. Because they could hold water, they were useful. But when it was too hot, or when people got tired, they would hang them in trees. The wind causes the vessels hanging from the tree to swing, and it's this movement that produces the sound of the whistling vessel. It helped them rest. That stayed with me. I found it beautiful. A quiet, useful gesture that created a space. Not something mystical or sacred. Just something gentle and functional. It was about comfort, about listening, about slowing down.

So Mitote comes from that image of a tree. I imagined a space that could evoke that same feeling. Somewhere to rest. Somewhere to be still. Not a shrine or ritualistic place. Just a calm space to contemplate. To sit with the object, to listen without being told what to think. The idea was to create an atmosphere where presence is enough. Where the object speaks through its simplicity, without needing to become something sacred.

Can you tell us about your daily rhythms? What keeps you grounded [or ungrounded] in Brussels? Any rituals, obsessions, or unexpected sources of energy?

I travel for work and to visit my family, but what really keeps me grounded in Brussels is the swimming pool. I’m a swimmer. I discovered swimming when I moved to Brussels because I was looking for an activity to connect with. Swimming quickly became my moment of care each week. It rewires my energy every time I go. I love the water, the feeling of breathing underwater, the silence. Sometimes I don’t listen to anything but my breath. It’s a practice that keeps me present and balanced.

At the same time, I’m not always grounded. I often find myself drifting into memories of Mexico, my childhood, and a deep nostalgia for those times. These memories make me a little volatile, especially when I’m not fully present. They pull me back to a different time and place, creating a contrast with my current life.

As for inspiration, there’s this album that came to mind unexpectedly. It’s Morton Feldman’s Rodko Chapel, specifically the fifth piece. The melody is hauntingly beautiful. It evokes private spaces, comfort, and memories for me. I imagine it could be the anthem of my own inner country. It’s like a safe place I carry with me. No matter what happens, I can always return to it.

What are some non-obvious references that feed your imagination? A book, a meme, a smell, a machine, anything that stays with you?

Yeah, but meme. I mean non-obvious ones. The YOLO thing. It's not the first time I mention it in an interview. You only live once. It’s true. When it first came up online, I thought it was just another internet joke. YOLO, YOLO, YOLO. But it stayed with me. It became a kind of principle. I like that it keeps things light. It reminds me not to take things too seriously. I really love the YOLO idea. It gives me space to relax and not overthink.

Books are harder to mention. There are too many images, too many possibilities. I am the kind of person who reads three at the same time and maybe finishes none. Or finishes one, then returns to another after a while. The last book I truly finished was Jung’s autobiography. The autobiography of Carl Jung. It is not complex. He just talks about his life, from his first memories to his later years. He wrote it when he was already old. It is a beautiful book. I was not familiar with psychoanalysis, but people around me kept saying I should read it. Everyone pushed me toward it.

It connects to something we spoke about earlier. Like the shadow. The famous shadow. I want people to keep their own interpretation. I love when they tell me what they saw, what they understood, what stayed with them. But I want them to remember what they want. I enjoy metaphors, analogies. When someone tells me they saw a huge onion, I laugh. I do not call it the onion. I call it the bulbous form. But maybe the bulb is an onion. That is how connections begin.

ÉCLIPSIS is a co-production by STUK, Botanique & Les Halles de Schaerbeek, FIBER & de Brakke Grond.

Photography SABINE VAN NISTELROOIJ

Interview by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next