Bendt Eyckermans

Bendt Eyckermans channels his interest in the vernacular into painting. The artist gives life to a body of work that houses the transformative quality of memory and the impermanence of emotions, exploring the ways these can be seen and understood. Bendt’s work expresses his genuine interest in life itself – and a rare faithfulness to the direct translation of lived experiences onto canvas. Embracing the ambiguity, nuance and mystery of human gestures and common circumstances, his paintings go beyond the intimacy he shares with his subjects. His works depict scenes where actions may appear conflicting or tense, and where identities are intentionally muddled. Far from being a portrait artist, he instead reclaims the power of contemporary painting to move past any figurative tradition. Bendt’s absorption in the vivid, narrative character of sculptural forms leads him to employ painting to inquire into depth and the monumentality of postures – he manages to stare straight into the eyes of the history of figurative art while maintaining a generative distance from it, endowing his works with a subtle sense of magic.

Your work catches the dynamism of gestures through the stillness and density of paint. There’s a sense of time passing and of being able to savor it in which feels calming – but also bleak and mysterious, precisely because of its transitory nature coupled with its certainty. Can you speak about the role of impermanence, slowness, and of retelling memories through your practice?

In essence, what painting is for me, is channeling certain emotions or personal events of significance on canvas. You could say that my body of work is a document of the zeitgeist that my generation carries. But to give you a more correct formulation: painting is me documenting myself and my existence in time on this earth.

I am not a creature of words, the imagery of the figuration are born from emotions and/or events that were for some reason of significance to me. Because of the impermanence or volatility of an emotion, having to paint daily is of utmost importance in the aid to process, isolate and translate certain feelings (or events) into my own vernacular on canvas.

On these paintings, when some time has passed, I later can reflect from a distance and place them in the time period of when, and to hopefully figure out why, they were made. Reflecting on them is key for me to verbalize the feelings that I had, again as an aid for me to understand myself and why I made these works. Of course, for the viewers these true meanings of most of the paintings that I produced will not be interesting. Because almost every painting is about my banal everyday life and personal moments with friends, family and loved ones which I formed into a hyperbolic imagery of the truth.

I guess the element of memory coming into the paintings and the process of painting also is an interesting subject in dialogue with your comment ‘... because of its transitory nature coupled with its certainty.’ Because for an individual a memory is the truth, while in fact it is in constant evolution. A memory is only the memory of what was perceived. And these characters or subjects in my paintings are placed and composed into a perpetual motion of stillness, forever bound to their place on the canvas. But forever in motion in the mind of the spectator or creator. What I mean with this is that I, as a human, am in constant development, whether it is personality-wise, political preferences, sexuality, etc. And while the subjects of the paintings carry specific meanings, they will also evolve in meaning once they will be accompanied with the associations I will connect to them in 20-30 years.

In relation to that sense of stillness, I like how the situations you depict are somewhat unassuming. In many of your paintings the subjects are not doing anything in particular; sometimes they’re resting, or are seized in the middle of common actions. What interests you most about your subjects and the culture you portray?

What interests me most is life itself, my way of looking at it and implementing scenes and details of it into painting. To take a banal subject and transform it into something that could trigger the imagination of a spectator.

For example, the subject of the painting The procrastination is in general about wealth and success. The main colors are chosen based on these 16th century paintings with the bucolic subject of a harvest, whose primary colors are green and yellow/orange (see De korenoogst by Pieter Bruegel the Elder). In those days when the harvest came there was the warmth of the spring and summer coming, and the prospect of income because of a good and healthy harvest. These colors, for me personally, invoke a happy mood and good vibrations. Just as the subject of my painting: laying there in the grass, like a farmer who takes his well earned rest under a tree wiping the sweat off his brow, without a single bother on his mind. While the totality of the work looks very bucolic and idyllic, a few rats are hiding in the surrounding grass and gazing at the subject, whose legs they are about to come and nibble on at any moment. Maybe this symbolizes that, while this person is happy and at ease, anything can happen in life, and nothing will completely go the way you hope or want it to. Or maybe this person is just simply laying in the grass and having a rest in a rat infested park.

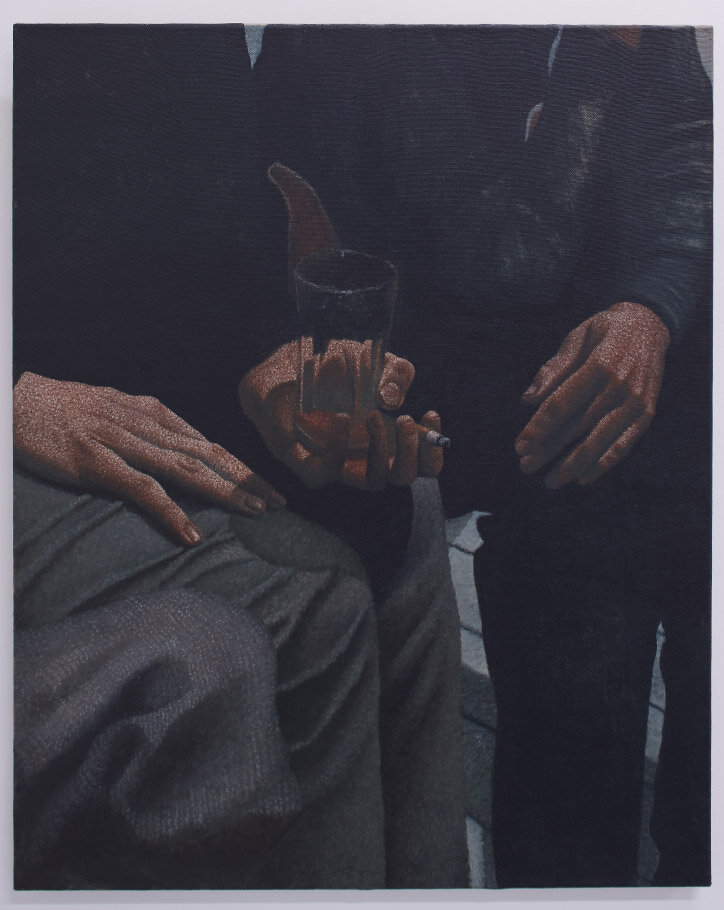

The figures in your paintings are almost never locking eyes with the observer. I personally feel like there’s an overabundance of the opposite dynamic – a sort of trope of ‘locking eyes’ between the represented subject and the observer – in our social imaginary. In your canvases gazes are mostly fleeting, and in several instances heads are either covered or out of the canvas. Hands, on the contrary, seem to have primacy over them. Contact, touch and body language seem to be pivotal elements in your work. How has your attention for such details evolved?

From childhood I have been surrounded by the sculptures of my family legacy. These sculptures, produced by my father, grandfather, great-grandfather and great-great-grandfather have inspired my interests in the art of sculpting throughout history, because of the discovery of what their own influences and inspirations were. To be more precise, my interest grew the most towards ancient Assyrian or Egyptian bas relief, linking their monumentality and way of storytelling on an “almost” two dimensional medium to my family legacy. This helped form the base of my compositions, stances and use of gestures by the subjects. The formation and monumentality of these ancient scenes, which could range from telling a simple story about farming peasants to a great epic spiritual poem, inspire me to transform banal everyday life subjects into a magical realism.

All the personas that you perceive in my paintings are all close friends or family members, who I then compose in these weird awkward stances, actions, moments of rest, etc. I then play around with power dynamics that fit the subject. I look for actions that you can never be too certain about, whether it is passionate or aggressive, a demand or a proposal, helpful or restraining. This dubiousness is an idea that I like to toy with, with the viewer in mind.

Having then sketched these compositions, I will start playing around with shifting them and deciding how I place them in their final form on canvas. I tend to prefer to not paint a face because at first hand it is something that was developed out of my shyness and awkwardness towards social encounters. But then it also functions for the fact that I don’t want to be labeled as a portrait artist.

Most of my paintings are very intimate with their subjects, atmospheres and emotions. And therefore, portraying a subject in full will make it a portrait about the given subject. I believe that hiding the face, or partially showing it, gives it more openness for a spectator to connect to it. There’s only one work that I can think of that in essence is truly a portrait of someone, and that is the painting A piece of mine. On the surface this work is about ambition and the distractions on the road towards your goal; I symbolically placed the monument of the museum of fine arts in Antwerp on the background symbolizing my ambition to be a part of the Belgian cultural heritage. But on a deeper level, this work is about acknowledgement. Portrayed is the daughter of the son that my grandfather presumably had with another woman in secret. And in our family there has never been any verbal “official” confirmation on whether they are his legitimate children or not, so they never have received any acknowledgement for descending from the same bloodline. Hence the title ‘A piece of mine:’ the subject asking me for something personal, who distracts me off of the road of ambition towards my goal, and on the other side of the coin she is my cousin, asking for acknowledgement in being a legitimate family member.

In composing and applying the base sketch on canvas it is important for me that there has to be something “off” or unusual. Especially in the composition, so that it will feel right (if that even makes sense?). I believe this “off-ness” is important in contemporary figurative painting otherwise it is just simply tradition and it wouldn’t have a contemporary feel to me.

Maybe I can also add that my paintings today compared to the paintings produced three years ago seem to have evolved from subjects in a melancholic and urban setting towards a more natural, but still urban, organic depiction of life. While the subjects are still performing in the same mindset and atmosphere of three years earlier.

courtesy BENDT EYCKERMANS

interview VERONICA GISONDI

What to read next