External Pages

External Pages was launched in 2018 by Ana Meisel—London-based digital artist, web developer and all-round interface whizz that co-runs creative technology studio 4 Us 4 Others. External Pages is a net.art platform that commissions artists to transform their ideas through and for the internet. For Ana, it all began with her passion for childhood blogging and customising web interfaces on Tumblr. Now she uses her skills to platform under-represented artists, providing the technical expertise and support needed to go digital.

Aware of the inequalities present online, External Pages is guided by cyberfeminist principles that scrutinise the ways in which the internet is “negotiated, managed, contested and contracted.” Each of its commissions can be traced to this central axis, exploring how issues such as gender identity, black visual culture, service work or intimacy influence digital space. The result runs riot through online orthodoxy, stretching the bandwidth of what is possible for digital artworks and interrogating the frameworks of online experience.

External Pages was launched in 2018 to support artists in the creation of ambitions net.art projects. The commissions you choose harnesses the instrumentality of computer technology with ideals of xenofeminist and anti-capitalist politics. Why did you start External Pages and what are the guiding philosophies that inform your commissioning process?

It’s funny to think about the reason behind starting External Pages because it’s excruciatingly basic. As a teen I found solace in blogging. I customised web pages and loved tailoring public spaces to my own accuracy. The difficulty in creating visuals via coding stimulated my fixation. After graduating from a BA Design course, being desperate for a future pushed me to think outside of what the internet has provided artists.

External Pages was a DIY initiative that wouldn’t cost anything. Artists could be free to show whatever they wanted publicly, and I could help to build that vision. I was reading a lot about cyberfeminism and internet art and understood the competitiveness of online spaces. A thought that stuck with me the most is from OurSpace: Taking the Net in Your Hands by Stephanie Bailey: “By nature, the internet—like real space—is not public at all. It is negotiated, managed, contested, and contracted.”

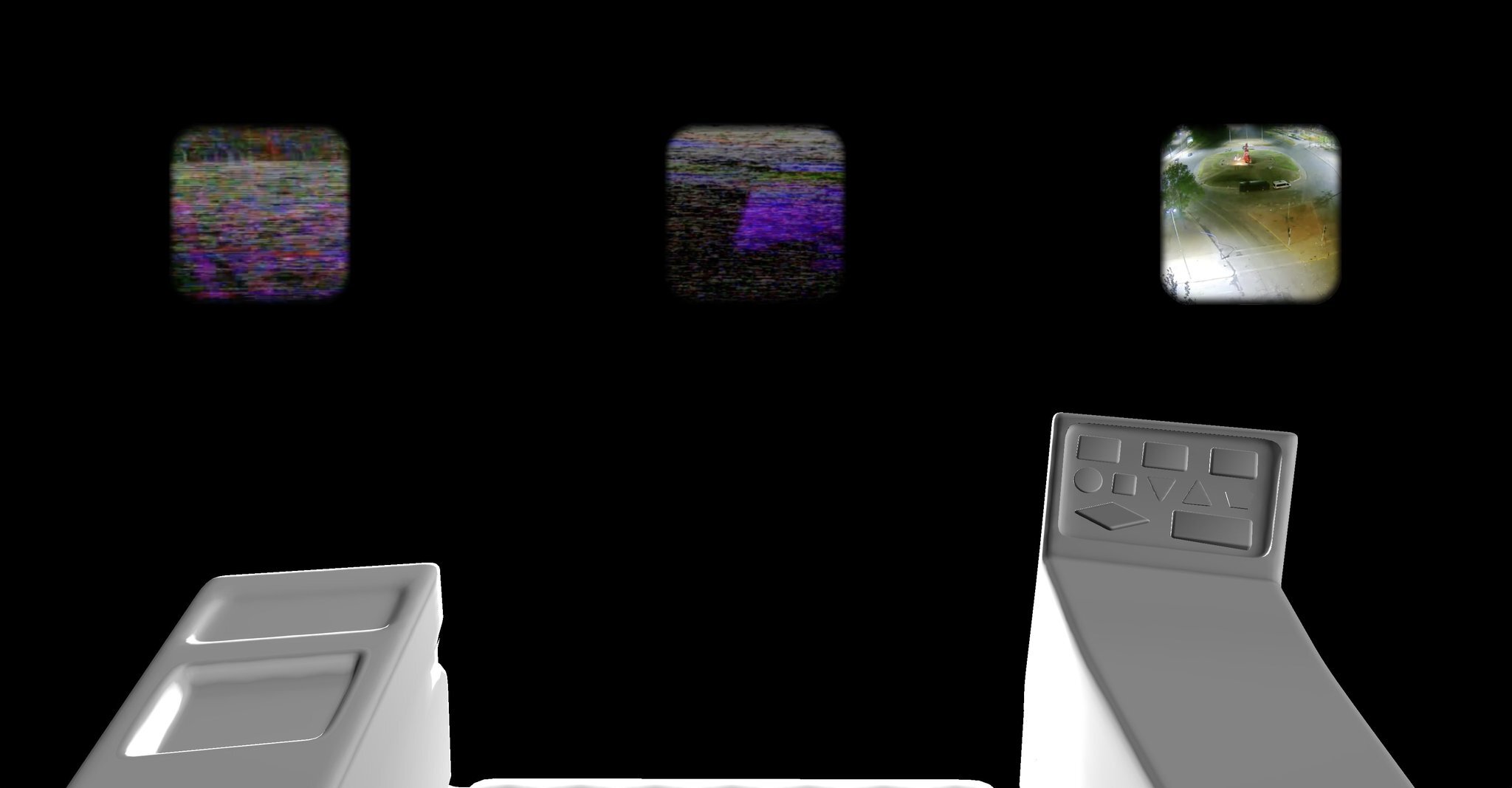

Your latest commission is from Camila Galaz, a Chilean-Australian artist based in Los Angeles. Focusing on the impact of COVID-19 on the current Estallido Social movement, we find ourselves navigating the online video-essay through a control panel interface found on the classic Tulip chairs of the Cybersyn Opsroom. How does Camila’s work bring together this piece of ergonomic 70’s cybernetica with the ongoing protests in Chile?

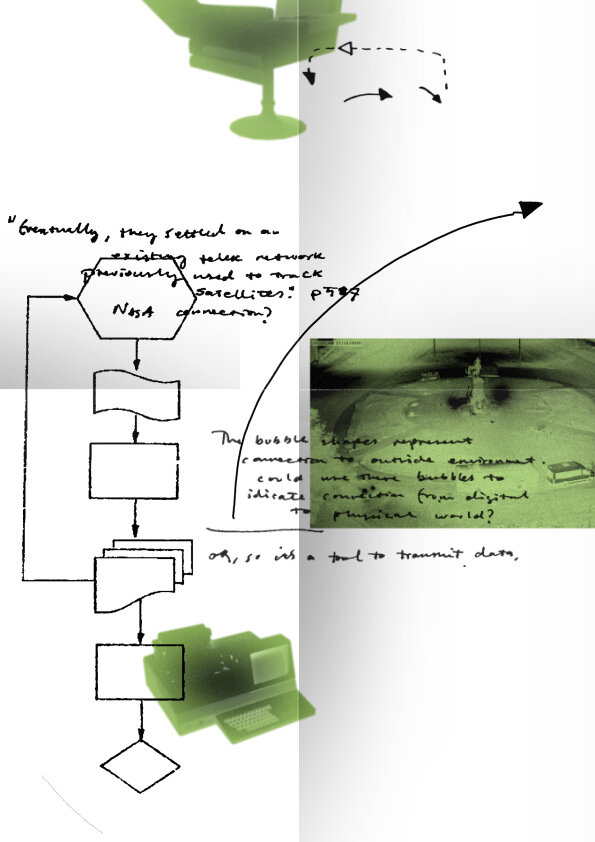

Project Cybersyn was a socialist technological project that aimed to create an automated system for the management of a national planned economy. Camila’s proposal made a comparison between the current protests and Cybersyn in order to add a historic perspective of Chile. Her piece, REDES: bread and justice, peaches and bananas, conveys what the Chilean demonstrators have done with platform technologies despite their neoliberal origin. Instagram, an app designed in principle for users to gloat, is now used to mobilise by voicing acts of state violence, and call-outs to demonstrate.

Placing protesting content against the Cybersyn interface, Camila communicates the strange evolution of these technologies. Cybersyn was conceived to distribute and equalise the economy, and capitalists gave us Instagram to protest capitalism. The significance of the ergonomic chair is that it is symbolic of the 60s and 70s when digital technology was first being publicly implemented. The 7 tulip chairs in the Cybersyn Ops room were distributed in a circle, so that the operators could interact with the screens on the walls via a control panel on the chair’s arm and then swivel around to communicate with their co-workers. This physical connectedness highlights how at odds our current technology is with cybersyn’s ergonomic ideology.

We haven’t made much technological progress since governmental tech projects like ARPANET, OGAS and Cybersyn. All big infrastructure projects—the computer, space travel, the Panama Canal—were created by governments. People argue that one of capitalism’s greatest inventions is the iPhone: a habit-forming device, made to stare at for as long as possible. We have a generation of people with internet addiction which has shown to decrease the wellbeing of people and increase suicide rates.

Using Camila’s project as an example, can you sketch out how the process works of supporting artists to produce new online works? In many cases, those you work with have little to no-experience in back-end coding or the experience in the digital languages required to create the artwork as we see it.

When I was first thirsty for the internet I understood the importance of distance from your art. That’s why collaboration is so important: you can distribute the weight of a project while giving each other space for perspective. I like working with people that are not weighed down by the difficulty of creating their vision, which is key to why External Pages works with artists that don’t necessarily code.

When Camila responded to External Pages’ open call her premise was fully developed, she had a clear vision of what she wanted to communicate and an idea of the general interface. Together we figured out the details of this interface and moulded it along the way. She would suggest interactions and I would explain how long it would take to make. I proposed user experiences, we discussed visuals, interactions and animations with graphic designer Effie Crompton, and usually called once a week to discuss updates and next steps. Sometimes artists need a stronger guide to realising their project, in which case I propose a few interfaces early on and why I think they work well with the theory. They then develop their thinking around these but it is up to them to decide on an ultimate direction.

Your previous commissions have looked at how issues including gender identity, black visual culture, service work or intimacy influence digital space. In your own experience, and from that of External Pages, how has the interface of the internet transformed in recent years to one where minority groups are often still-left at the receiving end of a typically white and masculine-coded environment?

There is so much bigotry that translates from offline biases to online. Just because something is automated or computerised doesn’t mean it’s progressive, which is what External Pages aims to highlight. In Uchronia et Uchromia, Rhea Dillon looked at the act of questioning: how it can be harmful and how the user’s passiveness can be challenged by appropriating this confrontation of questioning. Forms, questionnaires and tests are a perfect format for digitalisation and are often seized by institutions as surveillance and gatekeeping techniques. Dillon was able to make that really clear in this piece, while taking the concept even further and turning it back at the user, probing our deeper and sometimes subconscious instillings of white supremacist thought.

More broadly, which thinkers or artists have inspired you to explore counter-narratives to this online hegemony?

I am a big fan of Helen Hester’s writing around the automation of work and digitisation of femininity. She writes about the role of gender in work and how certain devices and apps adapt specific gender roles. This influenced my thinking early on when I noticed the awkwardness of transitioning labour into digital forms, and how that technologisation can reveal biases that used to be quite ambiguous. Asking Legacy Russell to work with her on displaying BLACK MEME on External Pages came out of my admiration for Russell’s Glitch Feminism where she explores how the embracing of the glitch filters into challenging our racial, gender and sexual biases. Another artist I’m fixated with right now is Katherine Frazer, who explores “the social implications of consumer technology”.

Recent developments in digital art have seen, on the one hand, the mundane and often-deceptive proliferation of press releases for “virtual exhibitions” hosted on Instagram, and on the other, the hyperinflation of ‘Nifties’ and other digital collectibles now available on blockchain networks. In each case, there is an implied or overt reification of “digital art” toward the solace of objects. In this light, why is it important for you to continue working with fidelity to the internet as a medium itself?

Instagram exhibitions are often unpaid, and the large amount of work artists put into these shows can be completely misaligned to the platform’s delivery, in terms of image quality and attention span. NFTs are a great way for artists to support themselves. The potential for sustainable income for digital artists is on the horizon. However, it is frightening how bad come NFTs and crypto art are, so I really don’t see it as a collective strategy. The average NFT has a carbon footprint equivalent to a EU resident’s total electric power consumption for more than a month, driving for 1000 km, or flying for 2 hours. NFTs have a strange way of valorising art as an end product. Why can’t people just pay digital artists for their labour and time? I think it all still sucks a bit. I’m eager for projects that are paced, well-informed and take the artist’s time into account.

What is next for External Pages?

In April we have a show with American artist, poet and meme-creator, Jenson Leonard. This will display an interactive selection of internet memes created under the artists’ online alias @coryintheabyss. The show is curated by Georgie Payne. After that—it’s unknown! I’m looking into more funding to continue the space. There have been some amazing submissions from very talented people, hopefully those will carry through. External Pages is always open for proposals and anyone can apply here → Google form.

interview CHARLIE MILLS

What to read next